George Stratford Seymour Cockburn

This post is part of a pilot student project created for the University of Florida class, Raising History from the Grave: Primary Historical Research in Literary Analysis and Public Humanities taught by Dr. Leah Rosenberg. The students focused on members of the Black Caribbean diaspora who worked on the Panama Canal or in the Canal Zone, the U.S. territory that surrounded the Panama Canal for much of the 20th century. These employees were originally classified as Silver employees because they were paid in silver currency as opposed to the Gold employees who were American citizens paid in gold currency. The term is still used today by both the community and scholars. The students worked with Pan Caribbean Sankofa, a community organization dedicated to preserving the history of Caribbean people in Panama, who identified community leaders as subjects for the project. Students consulted a wide array of archival materials in the Panama Canal Museum Collection and other institutions and learned how to use these resources to highlight individual accomplishments and connect lives to their larger communities through the digital humanities. For other posts, see Raising History from the Grave.

Introduction

George Stratford Seymour Cockburn was born on March 9th, 1889 in Kingston, Jamaica, to Norman and Jemima Cockburn. He grew up as the youngest of three surviving siblings in an important decade of Jamaican history marked by both modernization and economic hardship, and he built his career as a young man during a transformative period of time in the Caribbean and South/Central America: the construction of the Panama Canal. This venture is rightly valued as an engineering marvel of the Western world, but it also relied on the underpaid labor of thousands of West Indian Silver workers, including George Cockburn himself. Mr. Cockburn relocated to Colón, Panama with his wife, Amy, in 1914, and began working within the middle class of the Isthmus, largely in clerical positions that protected him from the grueling physical suffering other West Indians had to undergo. He advanced through the ranks of the Receiving and Forwarding Agency. He likely worked first as a warehouse checker, where he would have possibly collected and recorded measurements of cargo, and later as a clerk. He and his wife raised eight children, but the elder Cockburns died in the late 1920s or early 1930s when many of their children were still very young. The Panama Cockburn clan eventually moved to Rainbow City (previously Silver City), where they contributed significantly to the community, which is part of the reason his memory lives on today.

Jamaica & Early Life

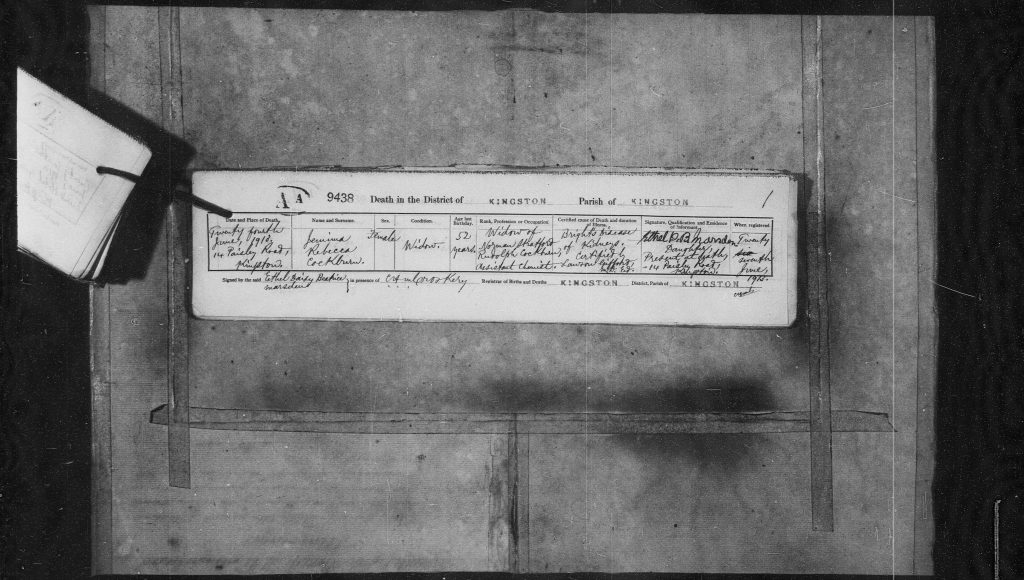

George Cockburn was born in Kingston in 1889 (birth record) to Norman and Jemima Rebecca Cockburn; while the latter’s name has been recorded with several variations, we have determined through frequency and signature analysis that this spelling and organization is the most accurate. George’s parents married in 1882 and had two children before George himself: Ethel Daisy Beatrice, born in 1884 (birth record); and Norman Stratford Rudolph, born in 1886 (birth record). They also had another son, Edmund Cyril Stratford, who likely was born and passed away in the same year, 1891 (death record).

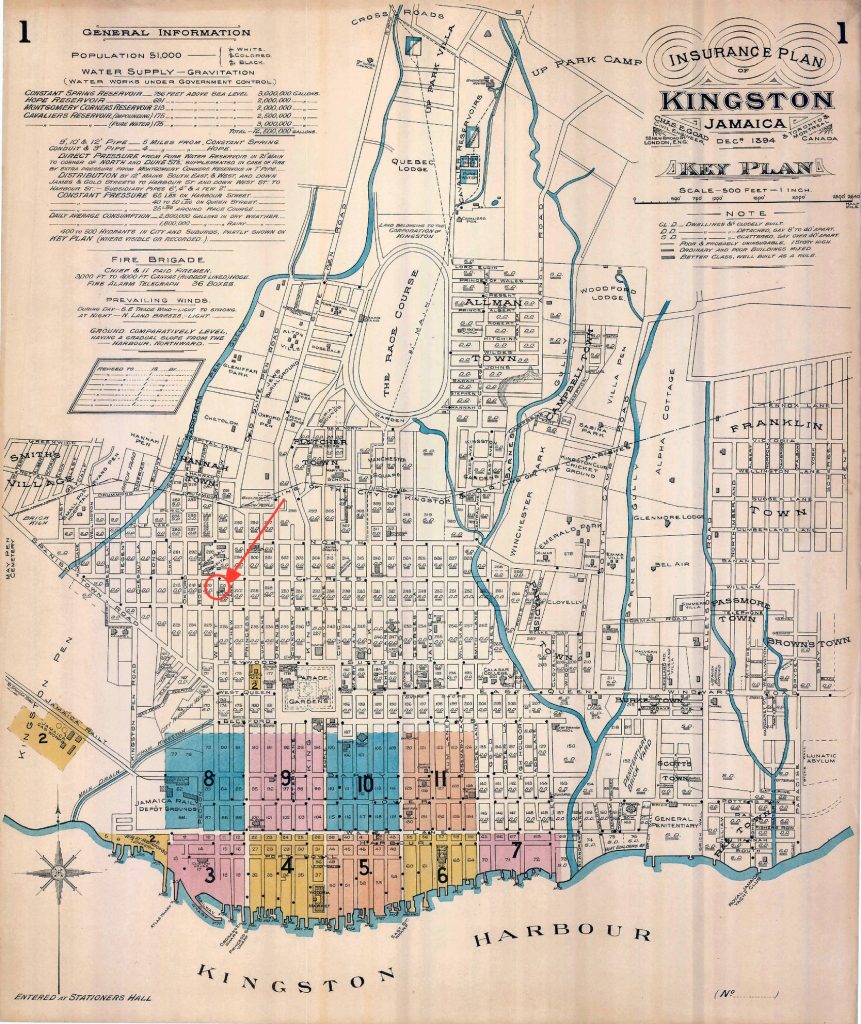

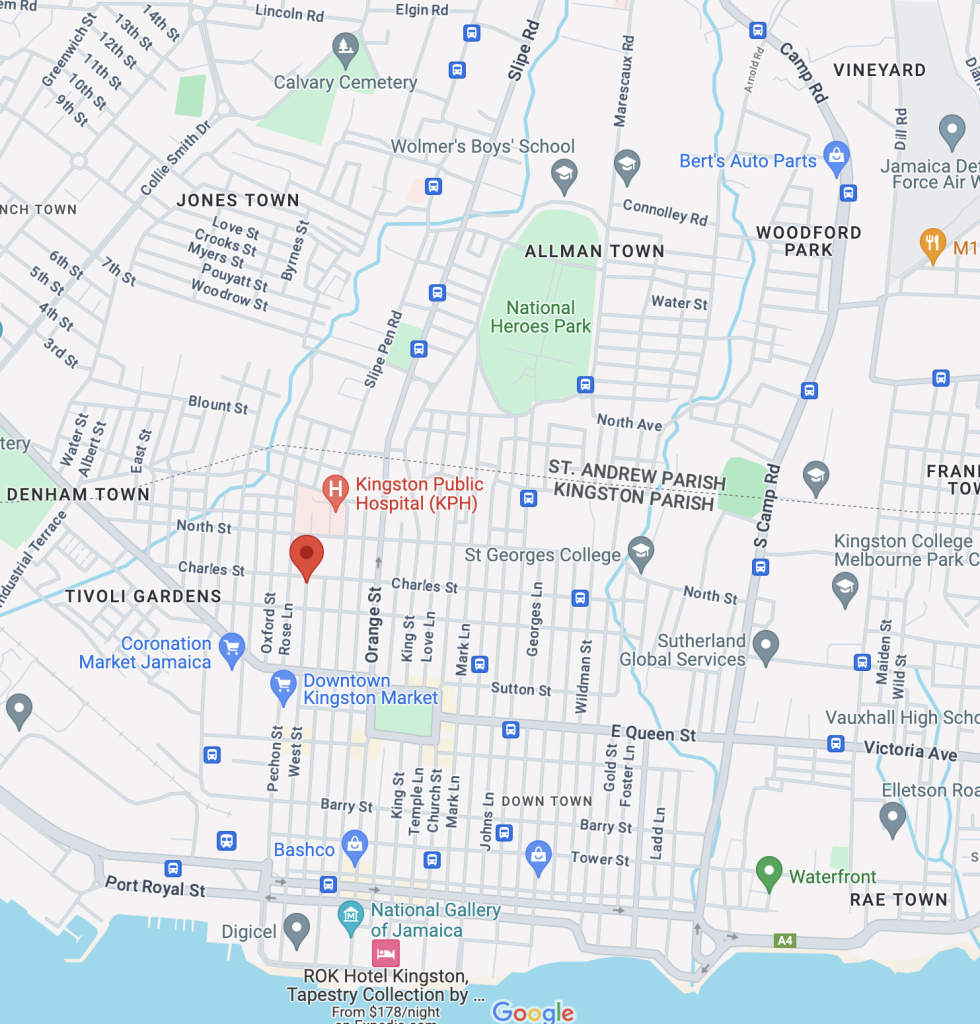

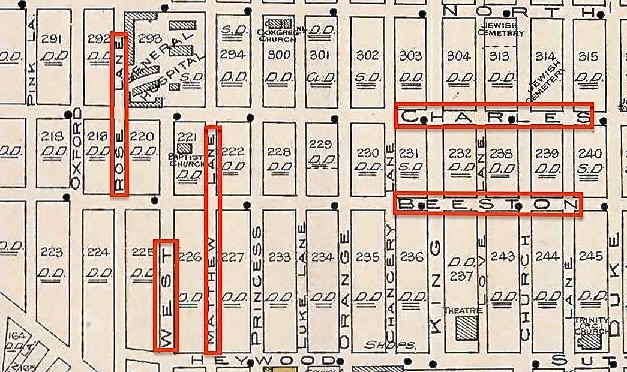

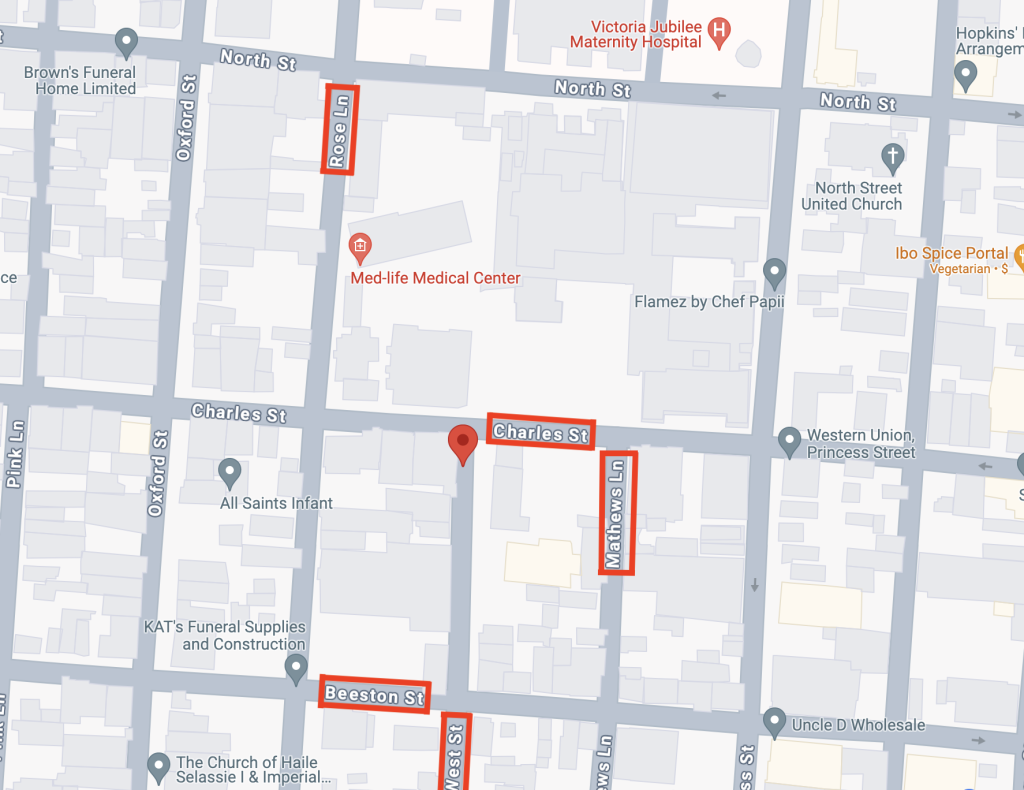

The Cockburn family lived at 145 West Street in Kingston, which can be seen on many of the documents provided. We were able to locate an 1894 insurance map (Insurance Map of Kingston, 1894) via Jamaican Family Search, which shows the entirety of Kingston as a city. By cross-referencing the street names with those on a current map of Kingston (accessed via Google Maps), we can determine that the Cockburns would have lived directly next to a Baptist church, the Kingston Public Hospital (est. 1776) and the Victoria Jubilee Maternity Hospital (est. 1892). Though the location is approximate, the two hospitals remain, and the neighborhood now seems to contain a funeral home and a clothing store as well.

As children, George and his siblings would have witnessed the decline of sugar and rise of banana plantations as Jamaica’s key industries (Modest & Barringer, p. 11), as well as diversification of the economy as other agricultural sectors began to rise with the flow of immigrants (Senior, p. 10). Some of the most important contributions to Jamaican society that would have affected George’s early life were the introduction of electricity, which occurred in 1892 via the Jamaican Public Service Company (Our History), and the Great Exhibition of 1891, which was intended to foster greater trade and communication between the United States and Jamaica (Jamaica International Exhibition, 1891).

Another interesting event of his childhood would have been attending the wedding of his sister Ethel to Walter James Marsden in 1905 (marriage record); this joyous occasion would have combined Anglican ceremonies with island rituals like the construction of arches made of palm leaves, traditional dancing and singing (Senior 21-22), and ‘carrying the cakes’ (Senior 510).

Olive Senior indicates in her book, Encyclopedia of Jamaican heritage, that despite the Anglicization of Jamaica, ‘country’ traditions, such as the usage of archways and festive cake-carrying, were notated as continuing as late as the 1930s (Senior, p. 21). This would have been an affair involving the entire family and church community, with everyone in the wedding party attending the next Sunday service to “turn thanks” (Senior, p. 511).

George and his family were members of the middle class in Jamaica and as such enjoyed a relatively rare social and economic status. His father, Norman Cockburn, was an Assistant to the Island Chemist, a municipal clerk position within the Department of Agriculture’s Government Laboratory. According to the 1921 Handbook of Jamaica, the Island Chemist worked alongside the Island Entomologist and Island Microbiologist to analyze data for medical and judicial purposes as well as for the public; the work of the Island Chemist was extended to involve agricultural research on sugar and rum in the early 1900s (Handbook, p. 221-222). Depending on when he began his position, Norman may have handled, categorized, and performed other clerical duties with the Royal Society of Arts and Agriculture’s articles on geology of the island, which was entrusted to the Island Chemist until the Public Library was formed in 1874 (Handbook, p. 226). Furthermore, Norman likely had amassed enough wealth to afford to legally marry his wife, Jemima Mack, which was also uncommon in a society marked more by domestic cohabitation than legal marriages due to the cost involved with the municipal proceeding and other financial expectations.

Norman’s unique economic position highlights the Cockburns’ special position within the social hierarchy of Jamaica, which was still quite stratified in the post-Emancipation period. But how did they rise to this station? Upon deeper research, we discovered that George Cockburn’s traceable roots extend far beyond this island. In the marriage register above, Norman’s father (and thus George S. S. Cockburn’s grandfather) is listed as George Alexander Cockburn. George Alexander Cockburn appears in a history of a Cockburn baronetcy of Langton in Berwickshire, Scotland entitled ‘The house of Cockburn of that ilk and the cadets thereof‘, a genealogical record of the family that shows the Cockburns’ migration to Jamaica and corroborates George Cockburn’s branch of the surname.

In the early 18th century, Doctor James Cockburn left Berwickshire behind for the tropical heat of the British colony and the fortune that lay in the sugar plantations that had, by then, reached their apex of profitability. It is important to recognize that the white Cockburns in Jamaica were certainly slave-owners–George S. S. Cockburn’s great-grandfather, Charles Seymour Cockburn, was listed in the Jamaican almanac as having 50 slaves on his St. Andrews plantation, Charlemount Penn, in 1833 (Jamaican Almanac, 1833). His son, George Alexander Cockburn, was the “heir presumptive” to the baronetcy, and was supposedly our George S. S. Cockburn’s grandfather.

For historical context, while slavery in the United Kingdom was abolished in 1808 and slavery in Jamaica was abolished in 1834 (The History of Jamaica), former slaves had to work in a four-year apprenticeship under their former masters due to the faux-benevolent idea of “equip[ping] formerly enslaved men and women to deal with their newly gained freedom as subjects (Modest & Barringer, p.5)”. Full emancipation did not occur until 1838, and economic disparities may have kept workers in their old jobs even longer than this.

While we do not know if she worked on the Cockburns’ plantations, we can speculate with fair certainty that Charles Cockburn’s son, George Alexander, had an extramarital relationship with an Afro-Jamaican woman, who gave birth to their son Norman Cockburn in 1854, George S. S. Cockburn’s father. Indeed, while the Jamaica marriage license lists Norman as George Alexander Cockburn’s son, the history of the Scottish “house of Cockburn” does not include Norman or his descendants (House of Cockburn 96-98), lending credence to the idea that his birth occurred outside of marriage. We hypothesize that George Alexander Cockburn assisted his son Norman by providing for the education necessary to become a clerk, and possibly offered further financial assistance; however, George Alexander Cockburn lived on the Charlemont plantation until his death (death record), while Norman moved away to the family home, so their relationship may not have been very close otherwise. However, George Alexander’s financial support would have allowed Norman and his children to avoid much of the persecution other Black working-class Jamaicans suffered in the post-emancipation period of Jamaican history.

Kingston and Jamaica as a whole modernized significantly between the time Norman was born and when George himself was growing up. However, in the early twentieth century, things for the Cockburn clan–and Jamaica as a whole–began to take a turn for the worst as the decade went on. In 1903, Norman, the family patriarch, died, leaving his son of the same name as the head of the house, as shown by his signing of the death document (death record).

Perhaps this was an indicator of things to come. In 1907, the Jamaican earthquake and subsequent fire struck. Englishman Vaughan Cornish described his own harrowing ordeal: “…the whole house was rocking violently; a fissure opened horizontally near the top of the west wall facing me, and a shower of brickwork fell near the threshold of the door… (Cornish, p. 246).” The devastating event caused tremendous damage to Kingston–approximately $2 million and twelve hundred lives were lost.

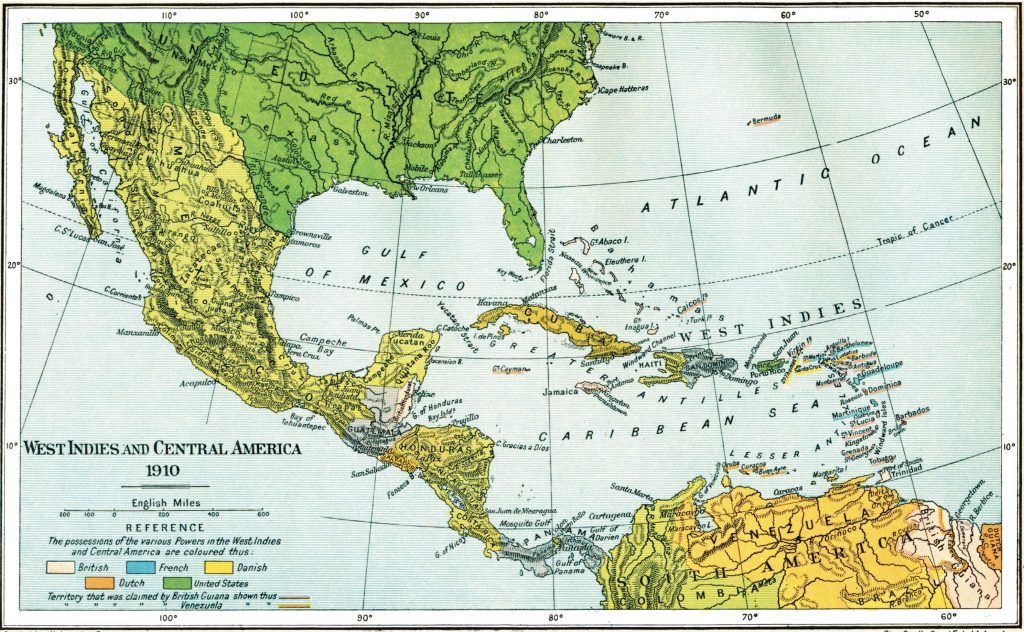

Mr. Cockburn departed for Panama sometime in early- to mid-1912, likely with his wife, Amy Barrett, on a Royal Mail Steam Packet Ship for the Panama Canal. While what exactly spurred his journey is unknown, a good hypothesis is that, with the declining economy in Jamaica, he likely wished to be able to provide a better life for his wife and future family. A strong migration pattern had also been established between the two countries, beginning in the 1850s with the construction of the U.S. railroad system and continued in the 1880s during the French phase of Canal construction (National Library of Jamaica). It was also more likely for a man of his socioeconomic status to be contracted, as travel to the Canal Zone required a $5 deposit under the Emigrants Protection Law of 1902, which would have “hamper[ed] the operations of the recruiting agents of the Isthmian Canal Commission (New York Times, 17 December 1905)”.

Life in Panama

In Panama, George Cockburn worked in various positions. He began his work in the Receiving and Forwarding Agency, commonly referred to as the R&FA (Photo Metal Check). R&FA was responsible for receiving and dispatching hundreds of thousands of tons of cargo from the time the Panama Canal opened throughout the period when Mr. Cockburn was in their employ (U.S. Annual Report 1921). During his time there, Mr. Cockburn worked in two different positions, first as a checker and then as a clerk. We concluded that this was the order in which he had these occupations, as we were able to verify his title of clerk six years after he came to Panama. In his position as a checker, Mr. Cockburn earned ¢.31 an hour (Metal Check). Instead of an hourly wage when he was a clerk, Mr. Cockburn earned $55 a month. Neither of these roles consisted of manual labor; rather, his job was mostly administrative in nature.

Holding a clerical position was relatively rare for West Indians – many of these roles were reserved for white Americans. This allows us to understand that, while Mr. Cockburn was a Silver worker and doubtlessly the victim of much discrimination, he nonetheless occupied one of the higher paying and desirable positions for West Indian workers at the time. Through a letter written from the Ambassador in Panama to the U.S. Secretary of State, we gain both general insight into the official government position towards West Indian workers and confirm that George Cockburn held a privileged position when compared to most West Indian workers at the time. The ambassador to the region, Seldon Chapin, wrote in 1954 that “although containing some minor clerical personnel, [West Indian labor] is largely composed of manual workers, both skilled and unskilled” (Office of the Historian). Despite the esteem of a higher ranked and important position, Mr. Cockburn was still limited to pay on the Silver roll (Photo Metal Check).

His personal life in Panama was much more difficult to uncover. Mr. Cockburn was married to Amy Burnett; although we cannot verify exactly when or where they were married, it is likely that their marriage occurred before they left Jamaica. We do know that once in Panama, they had many children together and cultivated a large family. According to the Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción records, we can see Amy, here spelled “Ami”, and George had their son, Erick Fitzgerald Cockburn, baptized in 1913, shortly after coming to Panama (Baptism record, 1913). In 1915, their son Leroy, officially Gilbert Carl Leroy, was baptized within the same church (Baptism record, 1915). Another child, Pearl Lera Cockburn, was born on June 14, 1917 (US Social Security, from Ancestry.com (subscription required)). A year later, in 1918, they had another son, Alden George, and in 1925, Lloyd Cockburn was born.

While we are unsure of exactly when Mr. George Cockburn passed, his son Leroy, then only 25 years old, was listed as the head of his household in 1940. In 1940, Leroy was listed as the head of a household made up of his siblings Alden, Amy, and Lloyd (1940 census, originally from FamilySearch), and Susan Hector, who may have been a maternal aunt. According to a personal interview with Canute Cockburn, George’s grandson, George and Amy ultimately had twelve children; however, at this time, these are the only progeny we have been able to verify. Additionally, an interview with George’s granddaughter, Casma Cockburn-Henlon, confirmed that only eight of the siblings survived past infancy.

While in Panama, Mr. Cockburn lived in Colón. As his residence fell outside of the official border of the Canal Zone, we do not have access to many records of that might show the exact neighborhood he lived in, his home, and other details. However, towards the end of his life, Mr. Cockburn was said to have moved to Silver City, Canal Zone (personal interview); we can estimate that this was no more than six years after the birth of his second son, Leroy, as the rest of his children were born in the Canal Zone (see above census). For the years after Mr. George Cockburn had passed and Leroy was designated head of household, more information about the exact location of his family exists. The building listed in the 1940 census was 185 Jamaica Street in Silver City, a home with three rooms and rent of $6.75 a month. Using the below map of Silver City, which we located via the University of Florida’s digital collection, and the information in the census from FamilySearch, we believe we were able to locate the precise location the Cockburns lived in in 1940: Apartment 6064F on Jamaica Street.

While we are not entirely sure when Mr. Cockburn passed away, a personal interview with Canute Cockburn asserts that the end of his life came when he was about 54 years old. This would have been sometime in 1943, but we have not been able to corroborate this date with paper data.

Mr. Cockburn’s Lasting Legacy

Mr. Cockburn was survived by many children and grandchildren, many of whom made significant contributions to their community. According to personal interviews with the grandchildren of Mr. Cockburn, his children were integral parts of many social advancements for West Indians. In Casma Cockburn-Henlon’s interviews, she stated that the surviving eight children were extremely close, in part due to their parents passing early in many of their lives. She noted that they looked up to one of the older siblings in particular: Mr. Leroy Cockburn, her father (47:40).

Leroy Cockburn was very involved both with his family and in the community. According to Mrs. Henlon, he began working as a “water boy” when he was thirteen (likely in 1928), probably to fetch drinks for Canal maintenance workers. As one of the eldest children, he took over as head of the household to provide for the rest of his siblings, as his older brother had left to attend seminary school in Jamaica. The 1940 census record also noted the family living with an aunt, Susan Hector. He married a woman named Dorothy and was depicted in this 1950 census as having had his first child, Lilia Cockburn.

Casma Henlon emphasized Leroy Cockburn’s community focus in an oral interview. “He helped so many people that I’m not aware of,” she said. “He was always encouraging someone, helping them to get on, to work with the [Canal] Company, or if they couldn’t do that trying to find a way that he could help them to improve their lot in life. He was everything in our church, from the door-opener to the accountant, a local preacher…, an organizer. He was active in the…local union, and a respected man. Everywhere that I went, they knew of the family, but they [really] knew of Leroy. And they respected him (46:36-47:34).”

“Everywhere that I went, they knew of the family, but they [really] knew of Leroy. And they respected him.”

-Casma Cockburn-Henlon

There are many extant newspaper clippings that demonstrate Mr. Leroy Cockburn’s commitment to his community. He was an officer of the Civic Council of Silver City, in the Camp Coiner-Mount Hope District (Panama Canal Spillway 30 Oct. 1964, 4). He also served as an installing master–and perhaps in other posts–with the Moonlight Club, which seemed to be a social club associated with the Methodist Church (Panama American 28 April 1945, 3), to which Leroy was also very committed to. Indeed, he was a society steward for the church who “served without remuneration” and encouraged others to attend the administrative quarterly meeting of the church dedicated to “diffusing the gospel to the large Methodist congregation on the Isthmus” (Panama American 11 Sept. 1958, 3). Indeed, Mrs. Henlon stated in her interview that her father “enriched his life by his service to God (49:31-49:35)”, and her whole family was deeply involved with the Methodist Church, which she speculated George and Amy would have also attended.

Lloyd Cockburn, who was born in approximately 1921, was another of George’s children who made important contributions to the community. Throughout the 1960s, Lloyd Cockburn wrote numerous letters to the government and pushed for the rights of women to work on piers. Lloyd was also instrumental in bringing the National Maritime Union to Panama, which helped protect workers’ rights.

Along with Lloyd, another one of George’s children, Holden, belonged to and was active in both the union and civic council (Panama Canal Spillway, 5 Nov 1965, 4). Holden also served as a professor at Rainbow City High School.

Finally, although we have been unable to entirely verify Harmon Cockburn as a member of George’s lineage, we surmise he was one of the children and know he also served as the Maritime Union Delegate from the wharfs (Panama Canal Spillway, 7 June 1963, 4).

We would like to extend special thanks to Mr. Cockburn’s grandchildren, Casma Cockburn-Henlon and Canute Antonio Cockburn, who have contributed invaluable information through their personal interviews. Alongside the extant archival information, their words have allowed us to construct a rich history of Mr. George Stratford Seymour Cockburn and the legacy he left behind. Should anyone be interested in listening to the full oral histories, please visit Mrs. Henlon’s interview and Mr. Cockburn’s interview, which should be available soon.

Appendix: FamilySearch Documents

Due to FamilySearch requiring viewers to make an account to view their documents, we have decided to include an appendix of images we reference from the site in case viewers have trouble accessing them. We attempt to organize them here as they are referenced in the text.

Source Information

Image Sources

Alamy. Mid-1700s map of Port Royal and Kingston Harbour. 24 Mar. 2016. The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Limited, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/24/story-cities-9-kingston-jamaica-richest-wickedest-city-world. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Civic Council Slates Listed.” The Panama Canal Spillway, 30 Oct. 1964, pp. 1–4, https://dloc.com/UF00094771/00482/images. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Civic Council Elections Nov. 9, 10.” Panama Canal Spillway, 5 Nov. 1965, pp. 1–4, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00094771/00535/zoom/3. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Cleary, JW. Kingston After 1907 Earthquake, Jamaica. 2 Feb. 2017. The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Limited, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/feb/02/jamaica-in-the-1890s-in-pictures. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Colon Methodists To Hold Quarterly Meeting Saturday.” Panama American, 11 Sept. 1958, pp. 3–3, https://dloc.com/AA00010883/02668/images/2. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Department of Operation and Maintenance. Town Maps of the Northern and Southern Districts – Silver City. University of Florida Digital Collections, University of Florida, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00000074/00001/images/11. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Eslava Flores, Carlos Alberto. Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción de Barichara – 1. Biblioteca Virtual Del Banco de La República, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/carlos-eslava/id/115. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Eslava Flores, Carlos Alberto. Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción de Barichara – 2. Biblioteca Virtual Del Banco de La República, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/carlos-eslava/id/115. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Gente En La Noticia.” Panama Canal Spillway, 7 June 1963, pp. 4, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00094771/00410/zoom/3. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“JAMAICA TAXES EMIGRANTS.; $5 Required from Each Person Going to Panama Canal Zone.” New York Times, 17 Dec. 1905, pp. 22, https://www.nytimes.com/1905/12/17/archives/jamaica-taxes-emigrants-5-required-from-each-person-going-to-panama.html. Accessed 8 July 2024.

James Valentine & Sons. Street View, Kingston, 1891. 2 Feb. 2017. The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Limited, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/feb/02/jamaica-in-the-1890s-in-pictures. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Kingston Map 1. 2013. Jamaican Family Search, Jamaican Family Search Genealogy Research Library, http://www.jamaicanfamilysearch.com/Samples2/kgnmaps1894.htm. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“New Officers Take Posts at Meeting of Moonlight Club.” Panama American, 28 Apr. 1945, pp. 3–3, https://dloc.com/AA00010883/05572/zoom/2. Accessed 8 July 2024.

West Indies and Central America, 1910. 2009. Maps ETC, USF, https://etc.usf.edu/maps/pages/7600/7642/7642.htm. Accessed 8 July 2024.

FamilySearch and Ancestry.com Document Sources

Death of Edmund Cyril Stratford Cockburn – Kingston. Death Registers 1891, January 1892–September 1892 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5VT-9RBP?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1C-96S&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Death of Ethel Marsden – Kingston. Death Records 1964, 1965 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-994D-8LL1?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQVSR-VS81&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Death of George Alexander Cockburn, “Jamaica, Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880” • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6JLQ-F1QT. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Death of Jemima Cockburn nee Mack – Kingston. Death Registers , • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5VW-9419?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1M-W2J&action=view. Accessed 16 July 2024.

Death of Norman Stratford Cockburn – Saint Andrew. Civil Registrations 1902, 1904, 1903 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-95JR-ZGX?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP13-F7J&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Death of Norman Stratford Rudolph Cockburn – Cross Roads. Death Records 1953 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-894D-HHPZ?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQVSR-ZKKR&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Erick Fitzgerald Cockburn Birth Record – Catedral Inmaculada Concepción. Baptism Records • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GGBW-87R?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQG6X-3P81&action=view. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Ethel Daisy Beatrice Cockburn Birth Record – Kingston. Birth Records 1884 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-61X9-6RV?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXF1H-82X&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

George Stratford Seymour Cockburn Birth Record – Kingston. Birth Records 1889 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6579-9TW?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXF18-96D&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Gilbert Carl Leroy Cockburn Birth Record – Catedral Inmaculada Concepción. Baptism Records • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GGBW-Z78?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQG6X-MF62&action=view. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Marriage Register of Ethel Cockburn and Walter Marsden – Kingston. Marriage Records 1905 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5V6-Z5D?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1V-CGB&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Marriage Register of Norman and Jemima Cockburn – Kingston. Birth Record Indexes 1880–1896 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5V5-QB9?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1W-DRF&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Norman Stratford Rudolph Cockburn Birth Record – Kingston. Birth Records 1885 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-X3S9-6SF?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXF14-Q99&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Pearl Lera Evering U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 – Ancestry.Com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/30281541:60901?tid=&pid=&queryId=0c75ca51-1a83-4623-a9d4-db0787e32182&_phsrc=Owz41&_phstart=successSource. Accessed 8 July 2024.

United States Census, 1950: Cristóbal. Census 1950 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHJ-5QH4-2SZK?view=index&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

United States Census, 1950: Cristóbal. Census 1940 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9M1-L7FW?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AK4K1-YC7&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Other Sources

Barringer, T. J., and Wayne Modest. Victorian Jamaica. Duke University Press, 2018.

Chapin, Selden. “The Ambassador in Panama (Chapin) to the Secretary of State.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, 2024, history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1952-54v04/d640.

“Charlemount.” Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, UCL Department of History, 2024, www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/1690.

Cockburn-Hood, Thomas H. “The House of Cockburn of That Ilk and the Cadets Thereof.” Internet Archive, Scott and Ferguson, 1 Jan. 1888, archive.org/details/houseofcockburno00cockuoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

Cornish, Vaughan. “The Jamaica Earthquake (1907).” The Geographical Journal, vol. 31, no. 3, 1908, pp. 245–71. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1777429.

Cundall, Frank, et al. “The Handbook of Jamaica for …: Comprising Historical, Statistical and General Information Concerning the Island Compiled from Official and Other Reliable Records.” The Handbook of Jamaica for … : Comprising Historical, Statistical and General Information Concerning the Island Compiled from Official and Other Reliable Records., Govt. Print. Establishment, 1881.

Jamaica International Exhibition, 1891.Sciencens-15,217-217(1890).DOI:10.1126/science.ns-15.374.217.a

“Migration.” National Library of Jamaica Digital Collection, nljdigital.nlj.gov.jm/exhibits/show/colon-man-panama-experience/migration. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Our History.” JPS, Jamaican Public Service Company, 2018, web.archive.org/web/20190209140743/https://www.jpsco.com/our-history/.

Senior, Olive. Encyclopedia of Jamaican Heritage. Twin Guinep Publishers, 2004, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofja0000seni, Accessed 8 July 2024.

“The History of Jamaica.” Jamaica Information Service, 2024, jis.gov.jm/information/jamaican-history/.