Making Waves with the First Ocean to Ocean Flight over Panama

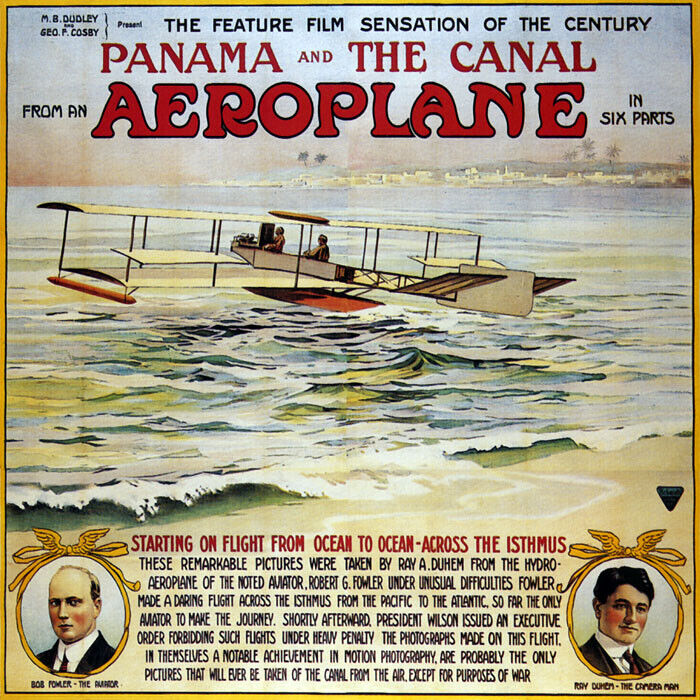

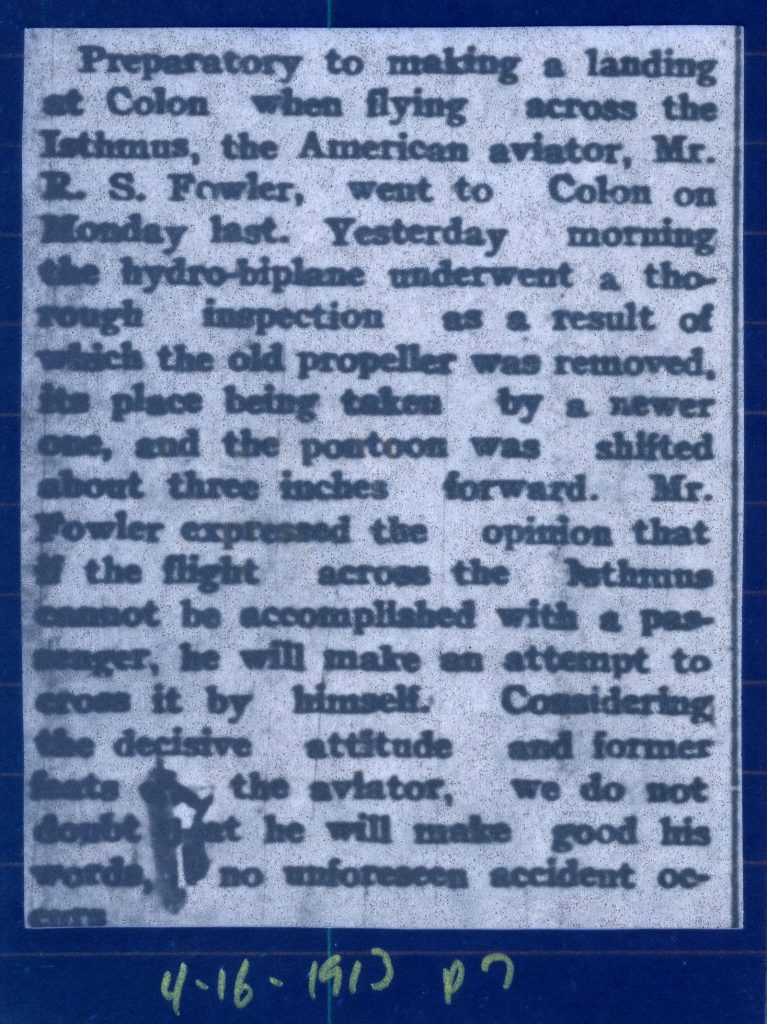

In April 1913 pilot Robert G. Fowler and cameraman Ray Duhem took the first non-stop flight across Panama, all the way from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. Their adventure was big news on the Isthmus, and was covered in the local press for the duration of their three week stay. In addition to being the first to accomplish the flight, they shot six reels of film that were to be released in theaters.

Things didn’t exactly go as planned…but lets start at the beginning.

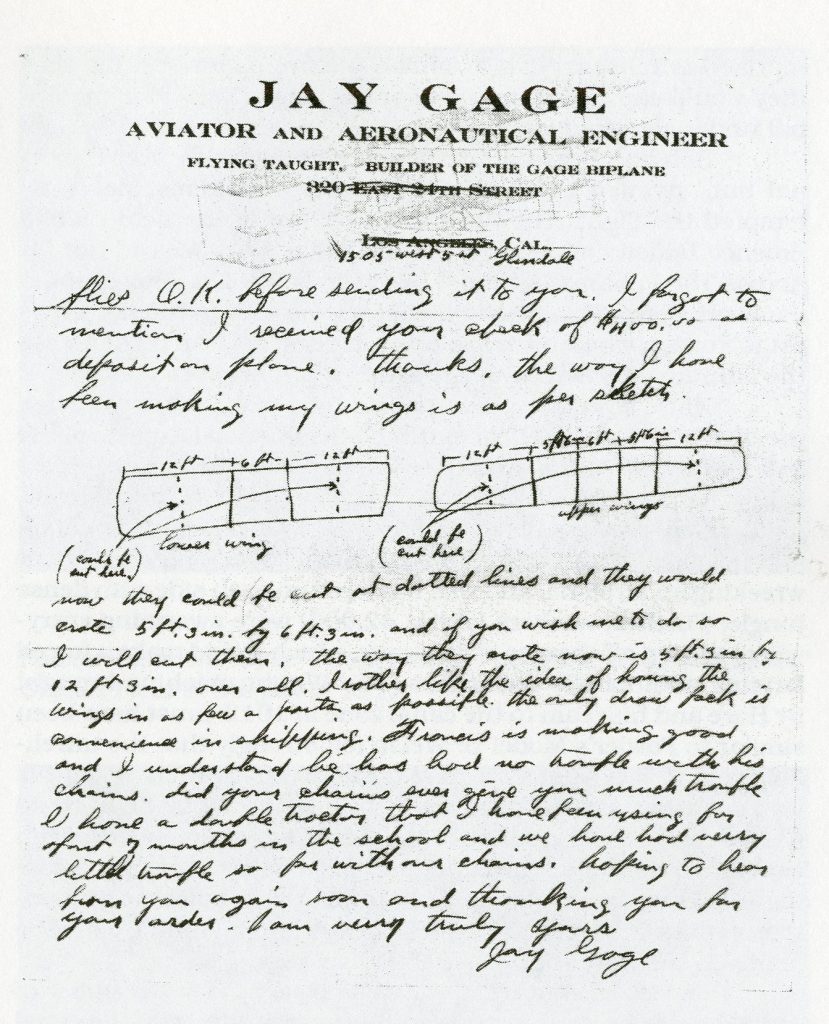

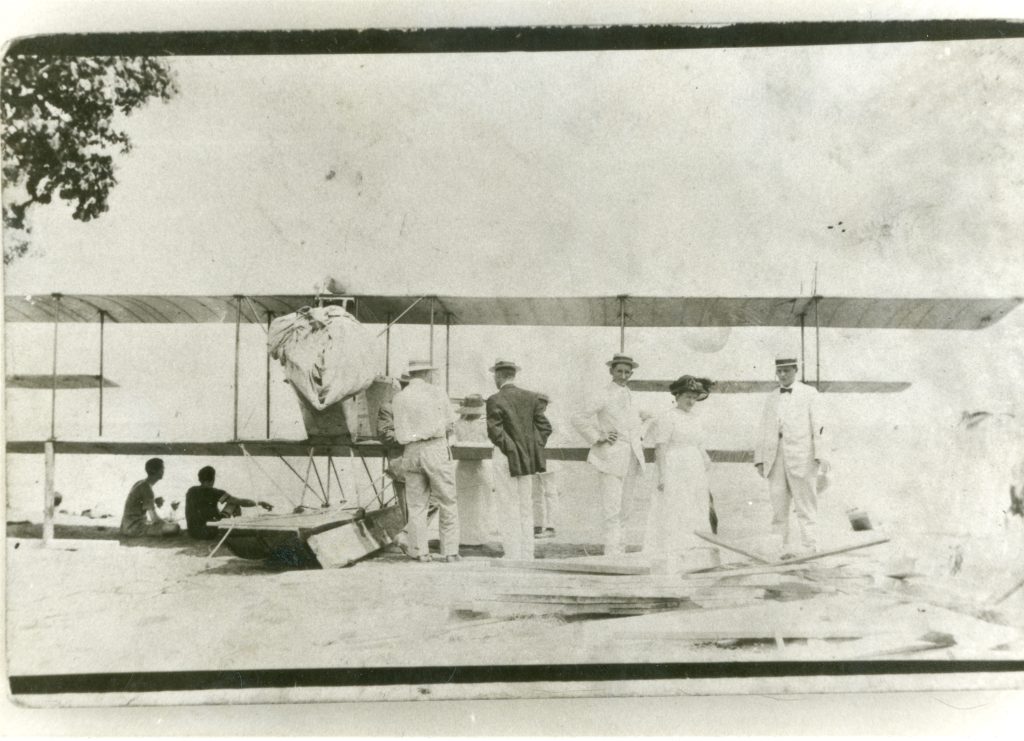

After becoming the first to fly coast-to-coast across the United States in 1912, Fowler started preparing for his flight across Panama. He and Jay Gage, a Los Angeles aeronautical engineer and aviator, collaborated on the design of a more powerful single propeller tractor biplane. Three significant design features were the passenger seat situated in-front of the pilot which would house the cameraman, the greater span of the upper planes on the wings, and the segmented manufacturing so that it could easily be crated for shipping to Panama. Because there were no airfields on either side of the route, wooden pontoons were affixed to the bottom, transforming it in to a hydroplane.

Note the dotted lines in the drawing which indicate where the planes of the wings could be cut for crating.1

Days before his departure Fowler learned the high-test fuel that the plane needed was not available in Panama. He quickly asked the Union Oil Company of California to ship 50 gallons on one of their tankers headed that way. After his two week trip, Fowler arrived to learn that the heat in the cargo hold had caused the tin cans to rupture and his fuel had evaporated. Luckily, the Panama Fire Department donated some of their own high-test fuel so the flight could continue as planned.

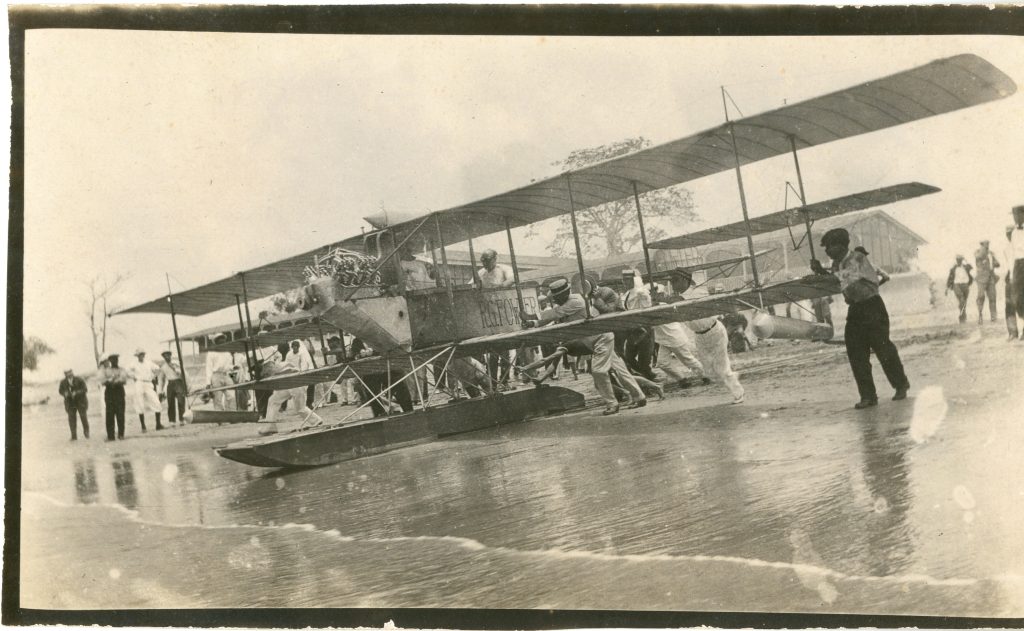

The airplane was transported to Bella Vista beach where it was assembled. Fowler commented on the dramatic Pacific side tides, “One big trouble on the beach I had set up as base was the large tide movement. At this point there was a 30 foot tide change – when the tide was out my plane was a quarter mile from the water.”2

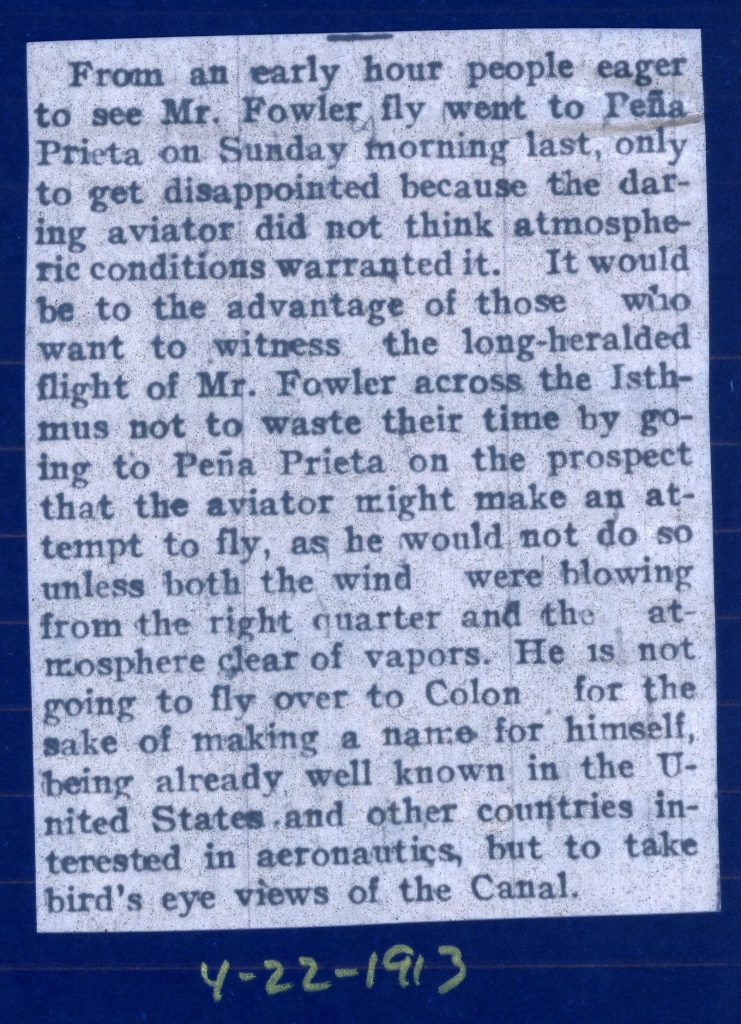

Fowler began test flights shortly after his arrival which were reported in local publications. Some flights were more harrowing than others and included mid-air stalls, a flooded and broken engine, near collisions with the shore, and a nude Duhem out on the pontoon spinning the propeller to help Fowler restart the engine. The newspapers didn’t report on many of those details, so to learn more about the test flight mis-adventures read The Life of Robert G. Fowler by Maria Schell Burden.

Use the left and right arrows to move through the slideshow of clippings from the Robert J. Karrer Papers.

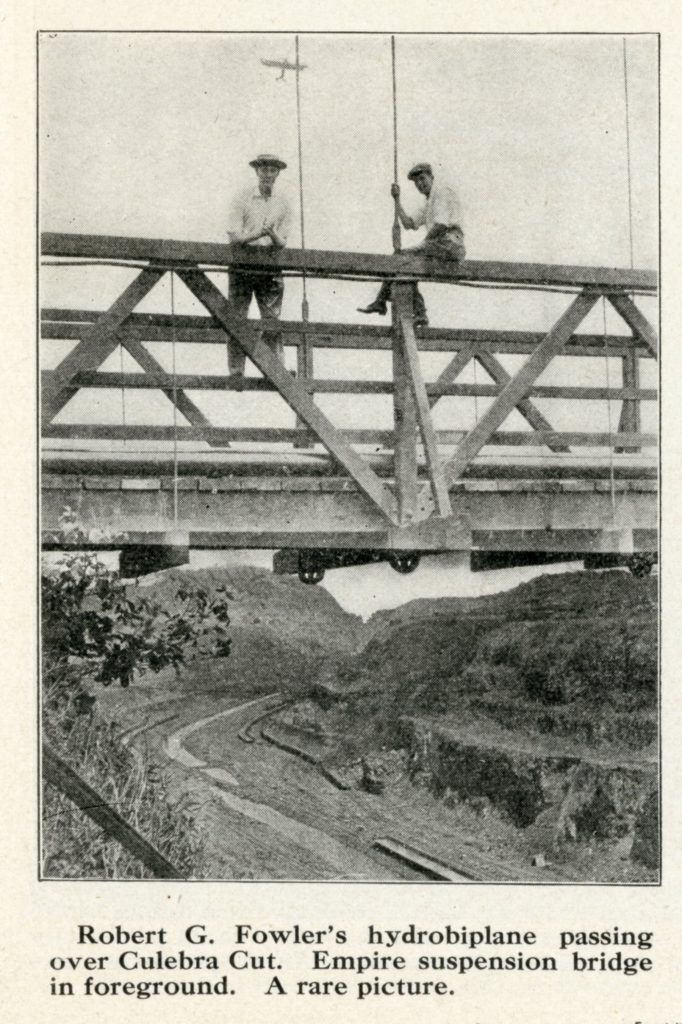

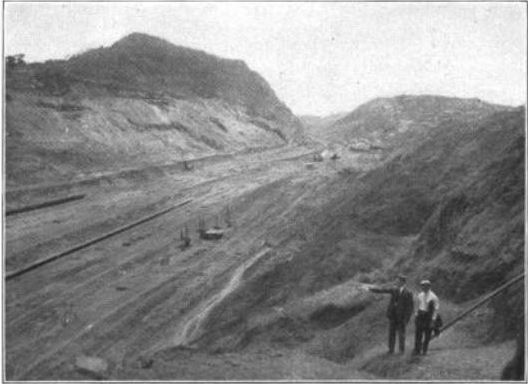

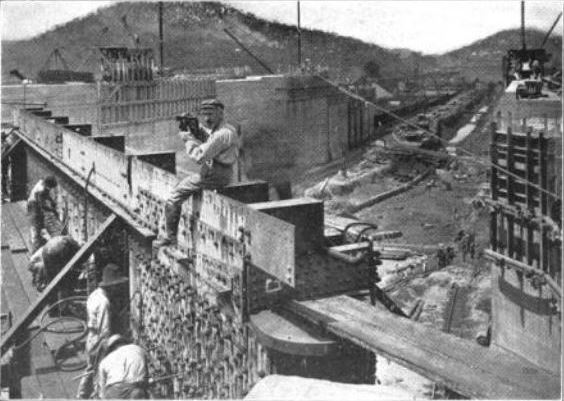

Fowler and Duhem made their historic trip on April 27th, 1913. While flying over Culebra Cut they were captured in the background of a photograph.

As they approached the end of their hour and 45 minute long flight, right over Cristobal, they ran out of gas and the engine stopped. Fowler was successful in guiding the plane to a landing spot in shallow water.

The image on the right is taken from America’s Triumph at Panama by Ralph Emmett Avery, 1913. Come check out the book in our Latin American and Caribbean Collection Library, https://ufl-flvc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01FALSC_UFL/6ad6fc/alma990227615780306597

Below is some of the footage that Duhem shot from the plane. You can watch them fly over Canal Zone towns and the construction site of the Canal. At minute 10:23 you can see the moment they run out of gas and the propeller stops in the film’s frame!

Near the end locals come out to greet them and help pull the plane on shore. The young ones have fun waving at the camera, just like they do today.

Despite the harrowing achievement, the real drama was yet to come.

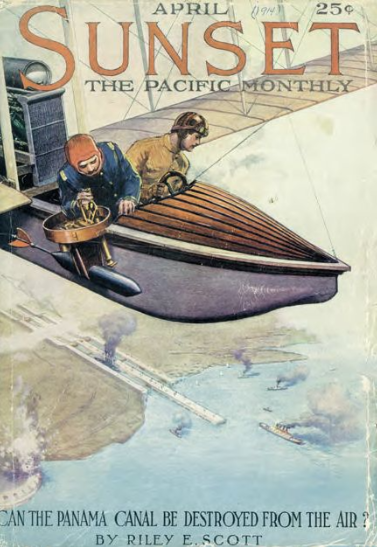

Charles Kellogg Field was the editor of Sunset The Pacific Monthly in April 1914 when the article about Fowler and Duhem’s flight was published. He and other aviation enthusiasts had concerns that Congress did not fully appreciate the importance and potential danger of airplanes. The author of the article, Riley E. Scott, was a West Point graduate and bombing expert who realized that their flight exposed a weakness in the Canal’s defenses. The cover caused quite a stir.

The image on the left is the cover of Sunset The Pacific Monthly, April 1914 issue. II.2019.999.249.

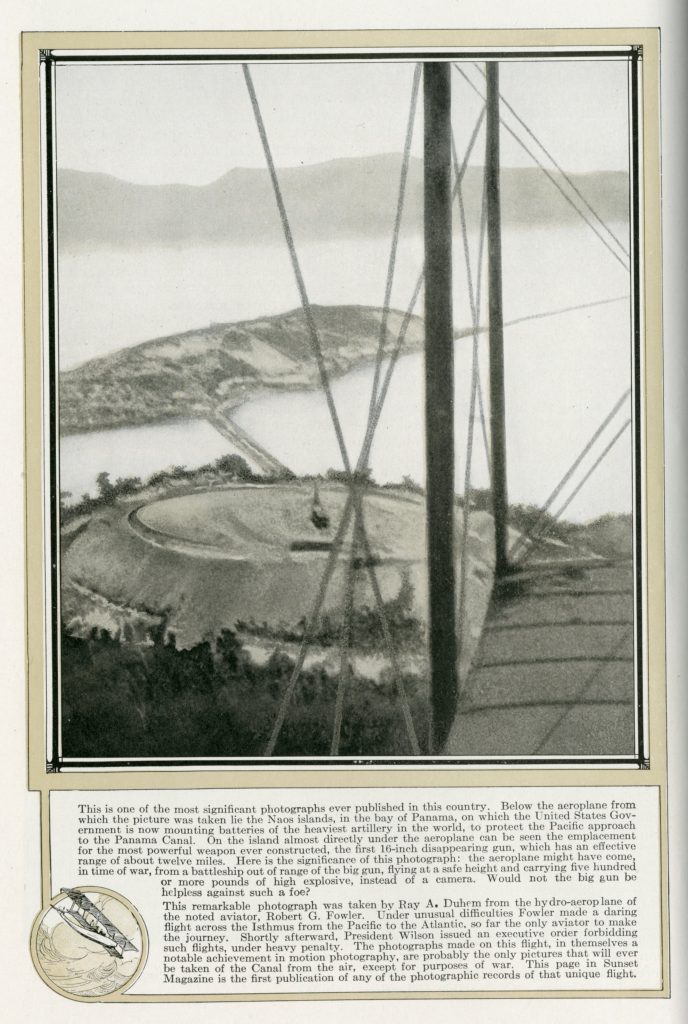

Three months after publication, at the request of the War Department, Fowler, Duhem, Scott, and Field were arrested and charged with spying by violating a statute that prohibited sharing military information. While filming the Canal’s construction Duhem had also filmed military installations. Scott included a still image of the future site for the 16-inch gun on Naos Island off the coast of Panama City in the article with a dramatic caption.

The men appeared in court and explained that they had been granted permission prior to the flight by both the War Department in Washington and by Colonel George C. Goethals, Chief Engineer of the Panama Canal construction. The case was dropped a year later.

The image on the right is taken from The Life and Times of Robert G. Fowler by Maria Schell Burden.

Fowler’s plane is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA. (minus the wooden pontoons damaged during the crash landing)

Two other efforts had been made to fly over Panama by different parties: O.G. Simmons, Al Welsh, and James H. Hare from Collier’s Weekly and Jesse Seligman. Neither group attempted the crossing. The Collier’s group cited lack of viable landing sites as a critical part of their decision. Severe air crosscurrents and wind were also dangerous elements. Fowler experienced the significant winds first hand on his flight. In one event an air current flipped the plane around so that it was flying in the opposite direction, and in another an air pocket over Culebra sent the plane plunging 300 feet straight down.

These images are taken from an article James H. Hare wrote in the Aero Club of America Bulletin called, “Why We Did Not Fly Across the Panama Isthmus.”

One Comment

Robert A Dryja

Such good history to see. The pictures remind me of when my grandfather was a policeman in the Canal Zone at that time. My daid was the assistant marine director in the 1950’s. He oversaw the widening of Galliard Cut to 500 feet and the adding of florescent lighting along the channel sides. Ships then could transit at the same time in both directions and also transit at night. As a child, I liked the florescent lighting for the variety and number of insects that flew around the lighting at night. They were another form of flight.