Student Contribution

-

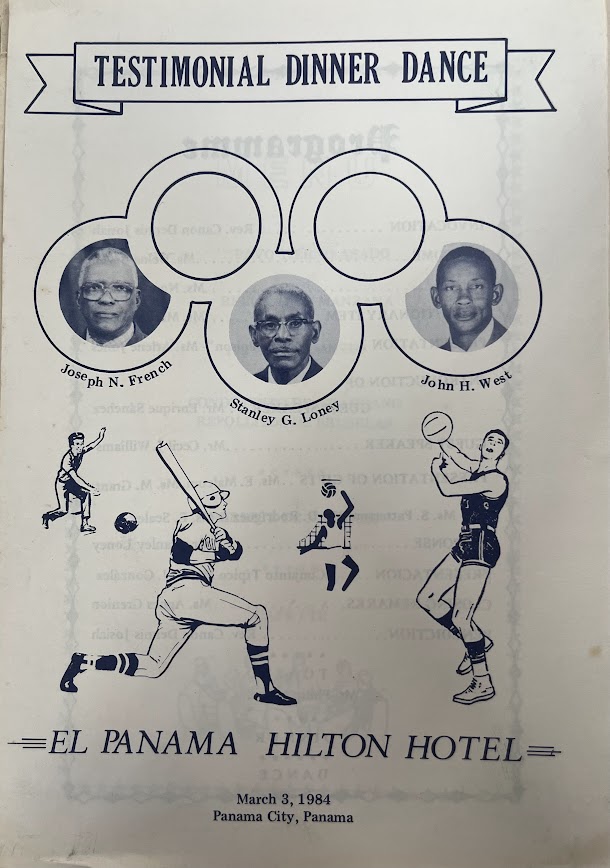

George Stratford Seymour Cockburn

This post is part of a pilot student project created for the University of Florida class, Raising History from the Grave: Primary Historical Research in Literary Analysis and Public Humanities taught by Dr. Leah Rosenberg. The students focused on members of the Black Caribbean diaspora who worked on the Panama Canal or in the Canal Zone, the U.S. territory that surrounded the Panama Canal for much of the 20th century. These employees were originally classified as Silver employees because they were paid in silver currency as opposed to the Gold employees who were American citizens paid in gold currency. The term is still used today by both the community and scholars. The students worked with Pan Caribbean Sankofa, a community organization dedicated to preserving the history of Caribbean people in Panama, who identified community leaders as subjects for the project. Students consulted a wide array of archival materials in the Panama Canal Museum Collection and other institutions and learned how to use these resources to highlight individual accomplishments and connect lives to their larger communities through the digital humanities. For other posts, see Raising History from the Grave.

Introduction

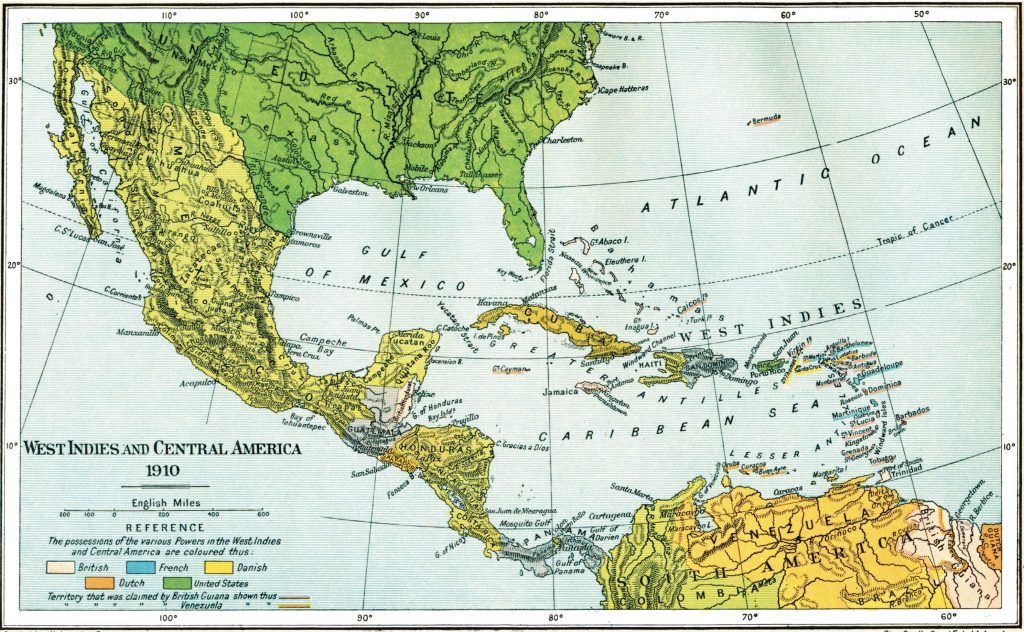

Map of Central America and Caribbean, 1910.

George Stratford Seymour Cockburn was born on March 9th, 1889 in Kingston, Jamaica, to Norman and Jemima Cockburn. He grew up as the youngest of three surviving siblings in an important decade of Jamaican history marked by both modernization and economic hardship, and he built his career as a young man during a transformative period of time in the Caribbean and South/Central America: the construction of the Panama Canal. This venture is rightly valued as an engineering marvel of the Western world, but it also relied on the underpaid labor of thousands of West Indian Silver workers, including George Cockburn himself. Mr. Cockburn relocated to Colón, Panama with his wife, Amy, in 1914, and began working within the middle class of the Isthmus, largely in clerical positions that protected him from the grueling physical suffering other West Indians had to undergo. He advanced through the ranks of the Receiving and Forwarding Agency. He likely worked first as a warehouse checker, where he would have possibly collected and recorded measurements of cargo, and later as a clerk. He and his wife raised eight children, but the elder Cockburns died in the late 1920s or early 1930s when many of their children were still very young. The Panama Cockburn clan eventually moved to Rainbow City (previously Silver City), where they contributed significantly to the community, which is part of the reason his memory lives on today.

Jamaica & Early LifeGeorge Cockburn was born in Kingston in 1889 (birth record) to Norman and Jemima Rebecca Cockburn; while the latter’s name has been recorded with several variations, we have determined through frequency and signature analysis that this spelling and organization is the most accurate. George’s parents married in 1882 and had two children before George himself: Ethel Daisy Beatrice, born in 1884 (birth record); and Norman Stratford Rudolph, born in 1886 (birth record). They also had another son, Edmund Cyril Stratford, who likely was born and passed away in the same year, 1891 (death record).

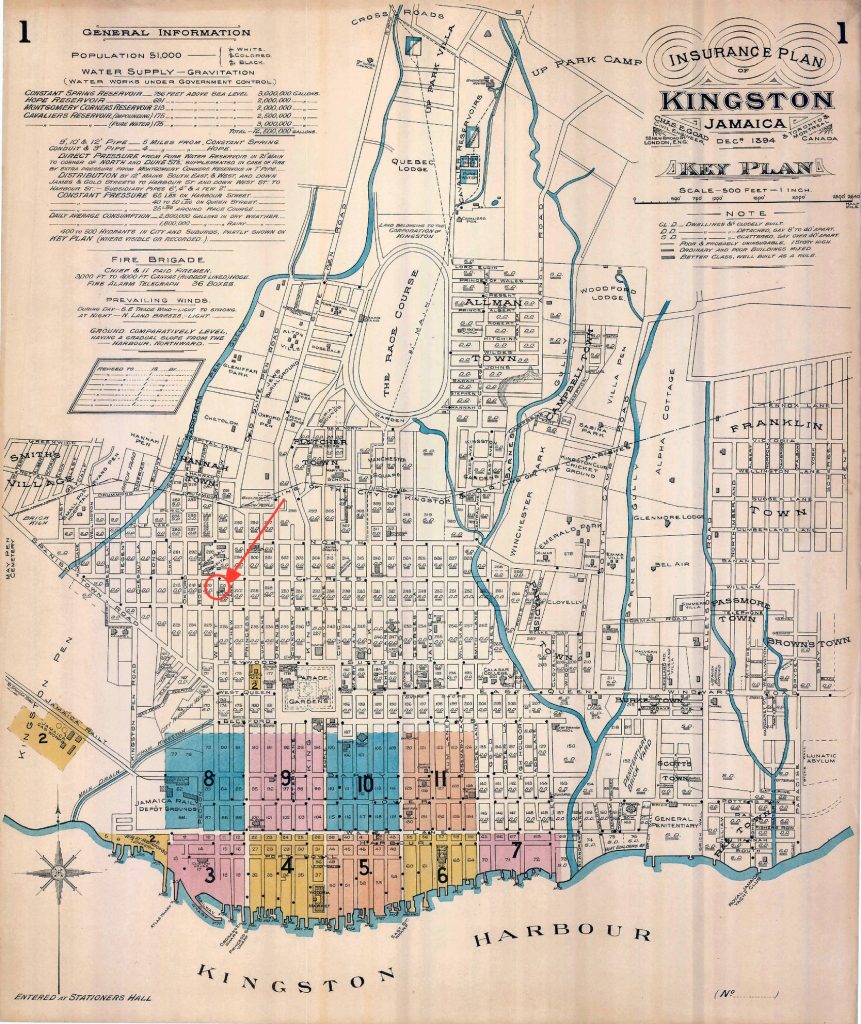

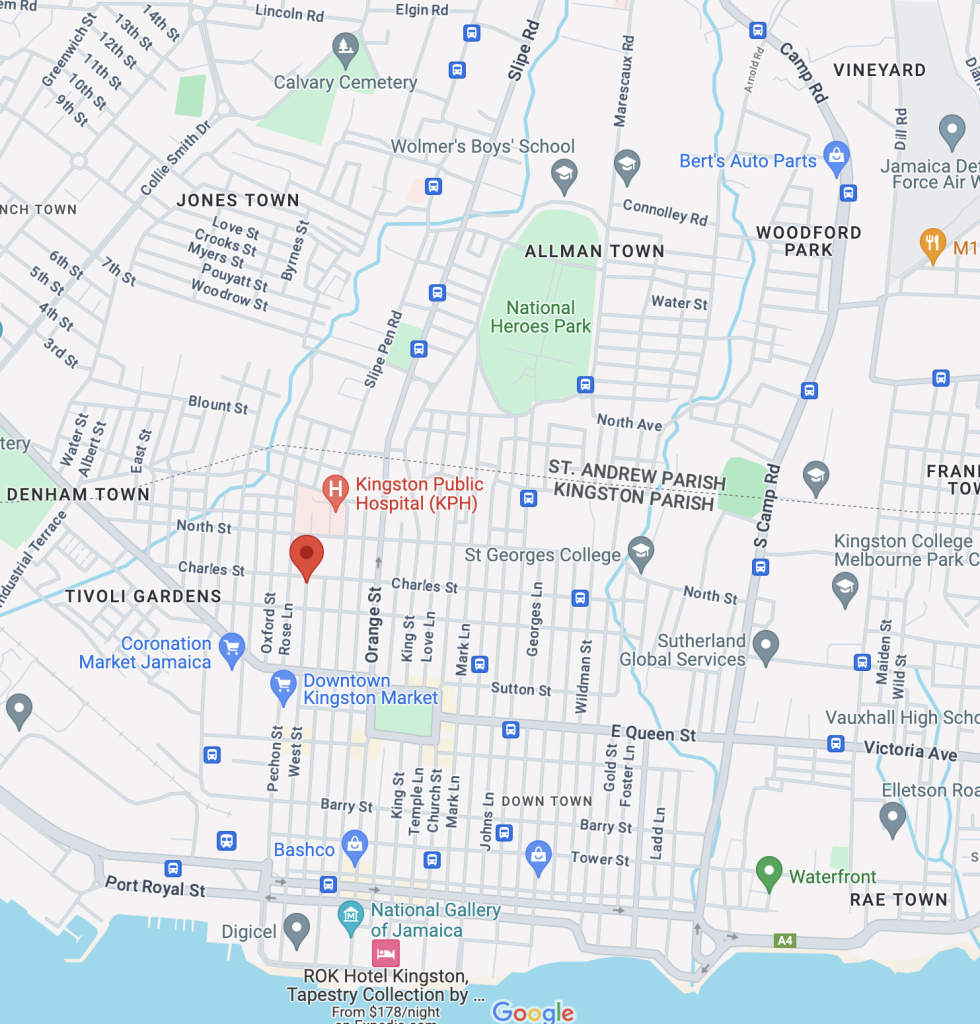

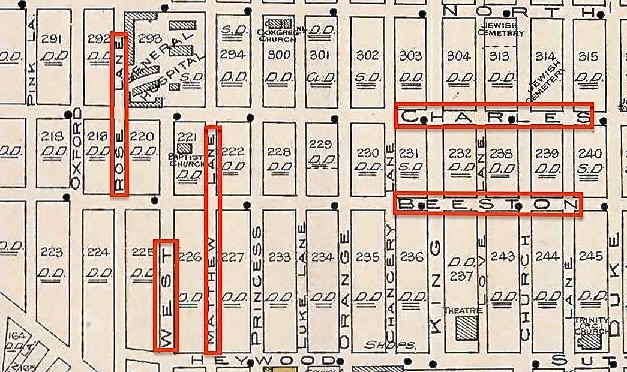

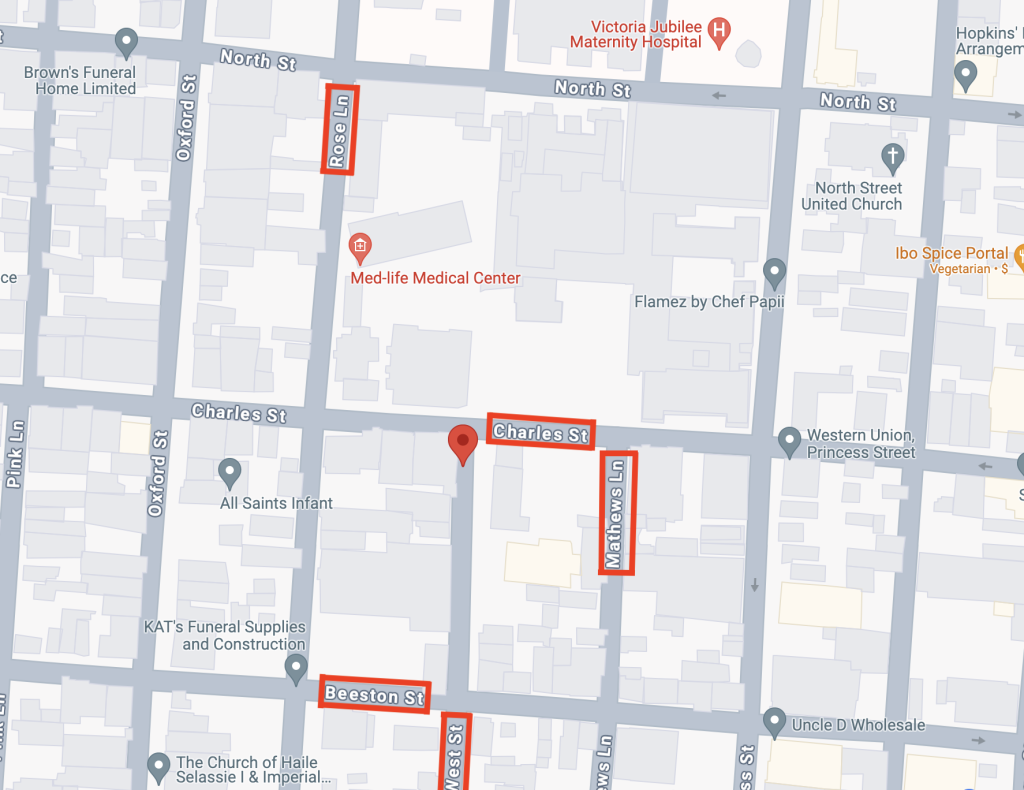

The Cockburn family lived at 145 West Street in Kingston, which can be seen on many of the documents provided. We were able to locate an 1894 insurance map (Insurance Map of Kingston, 1894) via Jamaican Family Search, which shows the entirety of Kingston as a city. By cross-referencing the street names with those on a current map of Kingston (accessed via Google Maps), we can determine that the Cockburns would have lived directly next to a Baptist church, the Kingston Public Hospital (est. 1776) and the Victoria Jubilee Maternity Hospital (est. 1892). Though the location is approximate, the two hospitals remain, and the neighborhood now seems to contain a funeral home and a clothing store as well.

As children, George and his siblings would have witnessed the decline of sugar and rise of banana plantations as Jamaica’s key industries (Modest & Barringer, p. 11), as well as diversification of the economy as other agricultural sectors began to rise with the flow of immigrants (Senior, p. 10). Some of the most important contributions to Jamaican society that would have affected George’s early life were the introduction of electricity, which occurred in 1892 via the Jamaican Public Service Company (Our History), and the Great Exhibition of 1891, which was intended to foster greater trade and communication between the United States and Jamaica (Jamaica International Exhibition, 1891).

Kingston, Jamaica in 1891. The Guardian.

Carrying the wedding cakes, early 20th century. Senior, p. 510. Another interesting event of his childhood would have been attending the wedding of his sister Ethel to Walter James Marsden in 1905 (marriage record); this joyous occasion would have combined Anglican ceremonies with island rituals like the construction of arches made of palm leaves, traditional dancing and singing (Senior 21-22), and ‘carrying the cakes’ (Senior 510).

Olive Senior indicates in her book, Encyclopedia of Jamaican heritage, that despite the Anglicization of Jamaica, ‘country’ traditions, such as the usage of archways and festive cake-carrying, were notated as continuing as late as the 1930s (Senior, p. 21). This would have been an affair involving the entire family and church community, with everyone in the wedding party attending the next Sunday service to “turn thanks” (Senior, p. 511).

George and his family were members of the middle class in Jamaica and as such enjoyed a relatively rare social and economic status. His father, Norman Cockburn, was an Assistant to the Island Chemist, a municipal clerk position within the Department of Agriculture’s Government Laboratory. According to the 1921 Handbook of Jamaica, the Island Chemist worked alongside the Island Entomologist and Island Microbiologist to analyze data for medical and judicial purposes as well as for the public; the work of the Island Chemist was extended to involve agricultural research on sugar and rum in the early 1900s (Handbook, p. 221-222). Depending on when he began his position, Norman may have handled, categorized, and performed other clerical duties with the Royal Society of Arts and Agriculture’s articles on geology of the island, which was entrusted to the Island Chemist until the Public Library was formed in 1874 (Handbook, p. 226). Furthermore, Norman likely had amassed enough wealth to afford to legally marry his wife, Jemima Mack, which was also uncommon in a society marked more by domestic cohabitation than legal marriages due to the cost involved with the municipal proceeding and other financial expectations.

Marriage record of Norman Cockburn and Jemima Mack, 1882. FamilySearch. Norman’s unique economic position highlights the Cockburns’ special position within the social hierarchy of Jamaica, which was still quite stratified in the post-Emancipation period. But how did they rise to this station? Upon deeper research, we discovered that George Cockburn’s traceable roots extend far beyond this island. In the marriage register above, Norman’s father (and thus George S. S. Cockburn’s grandfather) is listed as George Alexander Cockburn. George Alexander Cockburn appears in a history of a Cockburn baronetcy of Langton in Berwickshire, Scotland entitled ‘The house of Cockburn of that ilk and the cadets thereof‘, a genealogical record of the family that shows the Cockburns’ migration to Jamaica and corroborates George Cockburn’s branch of the surname.

In the early 18th century, Doctor James Cockburn left Berwickshire behind for the tropical heat of the British colony and the fortune that lay in the sugar plantations that had, by then, reached their apex of profitability. It is important to recognize that the white Cockburns in Jamaica were certainly slave-owners–George S. S. Cockburn’s great-grandfather, Charles Seymour Cockburn, was listed in the Jamaican almanac as having 50 slaves on his St. Andrews plantation, Charlemount Penn, in 1833 (Jamaican Almanac, 1833). His son, George Alexander Cockburn, was the “heir presumptive” to the baronetcy, and was supposedly our George S. S. Cockburn’s grandfather.

Map of Kingston and Port Royal harbors, ca. mid-1700s. The Guardian. For historical context, while slavery in the United Kingdom was abolished in 1808 and slavery in Jamaica was abolished in 1834 (The History of Jamaica), former slaves had to work in a four-year apprenticeship under their former masters due to the faux-benevolent idea of “equip[ping] formerly enslaved men and women to deal with their newly gained freedom as subjects (Modest & Barringer, p.5)”. Full emancipation did not occur until 1838, and economic disparities may have kept workers in their old jobs even longer than this.

While we do not know if she worked on the Cockburns’ plantations, we can speculate with fair certainty that Charles Cockburn’s son, George Alexander, had an extramarital relationship with an Afro-Jamaican woman, who gave birth to their son Norman Cockburn in 1854, George S. S. Cockburn’s father. Indeed, while the Jamaica marriage license lists Norman as George Alexander Cockburn’s son, the history of the Scottish “house of Cockburn” does not include Norman or his descendants (House of Cockburn 96-98), lending credence to the idea that his birth occurred outside of marriage. We hypothesize that George Alexander Cockburn assisted his son Norman by providing for the education necessary to become a clerk, and possibly offered further financial assistance; however, George Alexander Cockburn lived on the Charlemont plantation until his death (death record), while Norman moved away to the family home, so their relationship may not have been very close otherwise. However, George Alexander’s financial support would have allowed Norman and his children to avoid much of the persecution other Black working-class Jamaicans suffered in the post-emancipation period of Jamaican history.

Kingston and Jamaica as a whole modernized significantly between the time Norman was born and when George himself was growing up. However, in the early twentieth century, things for the Cockburn clan–and Jamaica as a whole–began to take a turn for the worst as the decade went on. In 1903, Norman, the family patriarch, died, leaving his son of the same name as the head of the house, as shown by his signing of the death document (death record).

Jamaica after the earthquake, 1907. The Guardian. Perhaps this was an indicator of things to come. In 1907, the Jamaican earthquake and subsequent fire struck. Englishman Vaughan Cornish described his own harrowing ordeal: “…the whole house was rocking violently; a fissure opened horizontally near the top of the west wall facing me, and a shower of brickwork fell near the threshold of the door… (Cornish, p. 246).” The devastating event caused tremendous damage to Kingston–approximately $2 million and twelve hundred lives were lost.

The Emigrants Protections Law of 1902 impacted US recruitment in Jamaica. NYT, 1905. Mr. Cockburn departed for Panama sometime in early- to mid-1912, likely with his wife, Amy Barrett, on a Royal Mail Steam Packet Ship for the Panama Canal. While what exactly spurred his journey is unknown, a good hypothesis is that, with the declining economy in Jamaica, he likely wished to be able to provide a better life for his wife and future family. A strong migration pattern had also been established between the two countries, beginning in the 1850s with the construction of the U.S. railroad system and continued in the 1880s during the French phase of Canal construction (National Library of Jamaica). It was also more likely for a man of his socioeconomic status to be contracted, as travel to the Canal Zone required a $5 deposit under the Emigrants Protection Law of 1902, which would have “hamper[ed] the operations of the recruiting agents of the Isthmian Canal Commission (New York Times, 17 December 1905)”.

Life in PanamaIn Panama, George Cockburn worked in various positions. He began his work in the Receiving and Forwarding Agency, commonly referred to as the R&FA (Photo Metal Check). R&FA was responsible for receiving and dispatching hundreds of thousands of tons of cargo from the time the Panama Canal opened throughout the period when Mr. Cockburn was in their employ (U.S. Annual Report 1921). During his time there, Mr. Cockburn worked in two different positions, first as a checker and then as a clerk. We concluded that this was the order in which he had these occupations, as we were able to verify his title of clerk six years after he came to Panama. In his position as a checker, Mr. Cockburn earned ¢.31 an hour (Metal Check). Instead of an hourly wage when he was a clerk, Mr. Cockburn earned $55 a month. Neither of these roles consisted of manual labor; rather, his job was mostly administrative in nature.

Holding a clerical position was relatively rare for West Indians – many of these roles were reserved for white Americans. This allows us to understand that, while Mr. Cockburn was a Silver worker and doubtlessly the victim of much discrimination, he nonetheless occupied one of the higher paying and desirable positions for West Indian workers at the time. Through a letter written from the Ambassador in Panama to the U.S. Secretary of State, we gain both general insight into the official government position towards West Indian workers and confirm that George Cockburn held a privileged position when compared to most West Indian workers at the time. The ambassador to the region, Seldon Chapin, wrote in 1954 that “although containing some minor clerical personnel, [West Indian labor] is largely composed of manual workers, both skilled and unskilled” (Office of the Historian). Despite the esteem of a higher ranked and important position, Mr. Cockburn was still limited to pay on the Silver roll (Photo Metal Check).

Taken from Mr. Cockburn’s Request for a Photo Metal Check (age: 29 years) His personal life in Panama was much more difficult to uncover. Mr. Cockburn was married to Amy Burnett; although we cannot verify exactly when or where they were married, it is likely that their marriage occurred before they left Jamaica. We do know that once in Panama, they had many children together and cultivated a large family. According to the Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción records, we can see Amy, here spelled “Ami”, and George had their son, Erick Fitzgerald Cockburn, baptized in 1913, shortly after coming to Panama (Baptism record, 1913). In 1915, their son Leroy, officially Gilbert Carl Leroy, was baptized within the same church (Baptism record, 1915). Another child, Pearl Lera Cockburn, was born on June 14, 1917 (US Social Security, from Ancestry.com (subscription required)). A year later, in 1918, they had another son, Alden George, and in 1925, Lloyd Cockburn was born.

Photos of Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción in Colón While we are unsure of exactly when Mr. George Cockburn passed, his son Leroy, then only 25 years old, was listed as the head of his household in 1940. In 1940, Leroy was listed as the head of a household made up of his siblings Alden, Amy, and Lloyd (1940 census, originally from FamilySearch), and Susan Hector, who may have been a maternal aunt. According to a personal interview with Canute Cockburn, George’s grandson, George and Amy ultimately had twelve children; however, at this time, these are the only progeny we have been able to verify. Additionally, an interview with George’s granddaughter, Casma Cockburn-Henlon, confirmed that only eight of the siblings survived past infancy.

While in Panama, Mr. Cockburn lived in Colón. As his residence fell outside of the official border of the Canal Zone, we do not have access to many records of that might show the exact neighborhood he lived in, his home, and other details. However, towards the end of his life, Mr. Cockburn was said to have moved to Silver City, Canal Zone (personal interview); we can estimate that this was no more than six years after the birth of his second son, Leroy, as the rest of his children were born in the Canal Zone (see above census). For the years after Mr. George Cockburn had passed and Leroy was designated head of household, more information about the exact location of his family exists. The building listed in the 1940 census was 185 Jamaica Street in Silver City, a home with three rooms and rent of $6.75 a month. Using the below map of Silver City, which we located via the University of Florida’s digital collection, and the information in the census from FamilySearch, we believe we were able to locate the precise location the Cockburns lived in in 1940: Apartment 6064F on Jamaica Street.

While we are not entirely sure when Mr. Cockburn passed away, a personal interview with Canute Cockburn asserts that the end of his life came when he was about 54 years old. This would have been sometime in 1943, but we have not been able to corroborate this date with paper data.

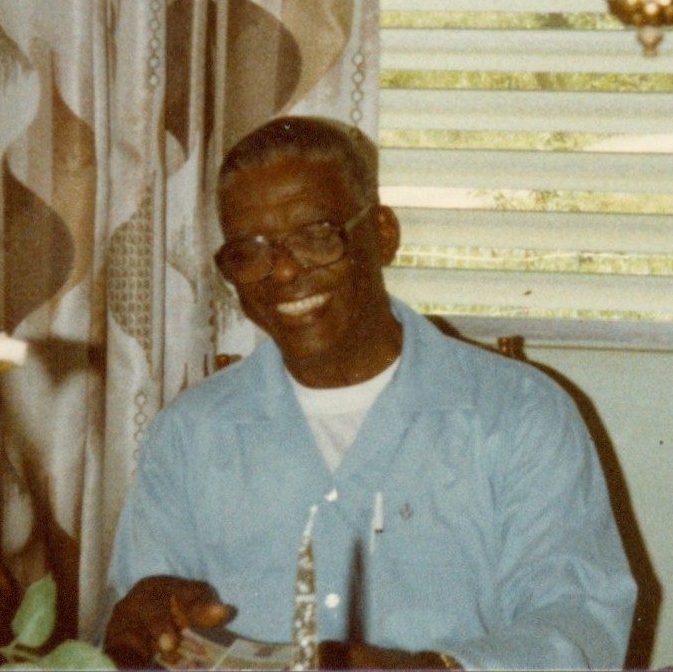

Mr. Cockburn’s Lasting LegacyMr. Cockburn was survived by many children and grandchildren, many of whom made significant contributions to their community. According to personal interviews with the grandchildren of Mr. Cockburn, his children were integral parts of many social advancements for West Indians. In Casma Cockburn-Henlon’s interviews, she stated that the surviving eight children were extremely close, in part due to their parents passing early in many of their lives. She noted that they looked up to one of the older siblings in particular: Mr. Leroy Cockburn, her father (47:40).

Leroy Cockburn was very involved both with his family and in the community. According to Mrs. Henlon, he began working as a “water boy” when he was thirteen (likely in 1928), probably to fetch drinks for Canal maintenance workers. As one of the eldest children, he took over as head of the household to provide for the rest of his siblings, as his older brother had left to attend seminary school in Jamaica. The 1940 census record also noted the family living with an aunt, Susan Hector. He married a woman named Dorothy and was depicted in this 1950 census as having had his first child, Lilia Cockburn.

Casma Henlon emphasized Leroy Cockburn’s community focus in an oral interview. “He helped so many people that I’m not aware of,” she said. “He was always encouraging someone, helping them to get on, to work with the [Canal] Company, or if they couldn’t do that trying to find a way that he could help them to improve their lot in life. He was everything in our church, from the door-opener to the accountant, a local preacher…, an organizer. He was active in the…local union, and a respected man. Everywhere that I went, they knew of the family, but they [really] knew of Leroy. And they respected him (46:36-47:34).”“Everywhere that I went, they knew of the family, but they [really] knew of Leroy. And they respected him.”

-Casma Cockburn-HenlonThere are many extant newspaper clippings that demonstrate Mr. Leroy Cockburn’s commitment to his community. He was an officer of the Civic Council of Silver City, in the Camp Coiner-Mount Hope District (Panama Canal Spillway 30 Oct. 1964, 4). He also served as an installing master–and perhaps in other posts–with the Moonlight Club, which seemed to be a social club associated with the Methodist Church (Panama American 28 April 1945, 3), to which Leroy was also very committed to. Indeed, he was a society steward for the church who “served without remuneration” and encouraged others to attend the administrative quarterly meeting of the church dedicated to “diffusing the gospel to the large Methodist congregation on the Isthmus” (Panama American 11 Sept. 1958, 3). Indeed, Mrs. Henlon stated in her interview that her father “enriched his life by his service to God (49:31-49:35)”, and her whole family was deeply involved with the Methodist Church, which she speculated George and Amy would have also attended.

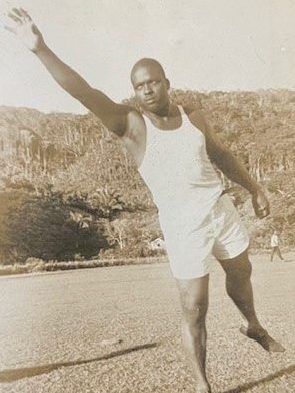

Lloyd Cockburn, who was born in approximately 1921, was another of George’s children who made important contributions to the community. Throughout the 1960s, Lloyd Cockburn wrote numerous letters to the government and pushed for the rights of women to work on piers. Lloyd was also instrumental in bringing the National Maritime Union to Panama, which helped protect workers’ rights.

Along with Lloyd, another one of George’s children, Holden, belonged to and was active in both the union and civic council (Panama Canal Spillway, 5 Nov 1965, 4). Holden also served as a professor at Rainbow City High School.

Article featuring Holden L. Cockburn’s election to the Rainbow City District Civic Council, p. 4. Finally, although we have been unable to entirely verify Harmon Cockburn as a member of George’s lineage, we surmise he was one of the children and know he also served as the Maritime Union Delegate from the wharfs (Panama Canal Spillway, 7 June 1963, 4).

We would like to extend special thanks to Mr. Cockburn’s grandchildren, Casma Cockburn-Henlon and Canute Antonio Cockburn, who have contributed invaluable information through their personal interviews. Alongside the extant archival information, their words have allowed us to construct a rich history of Mr. George Stratford Seymour Cockburn and the legacy he left behind. Should anyone be interested in listening to the full oral histories, please visit Mrs. Henlon’s interview and Mr. Cockburn’s interview, which should be available soon.Appendix: FamilySearch Documents

Due to FamilySearch requiring viewers to make an account to view their documents, we have decided to include an appendix of images we reference from the site in case viewers have trouble accessing them. We attempt to organize them here as they are referenced in the text.

Birth record of George Stratford Seymour Cockburn

Birth record of Ethel Daisy Beatrice Cockburn

Birth record of Norman Stratford Rudolph Cockburn

Birth/death record of Edmund Cyril Stratford Cockburn

Marriage record of Ethel Cockburn and Walter Marsden

Marriage record of Norman Stratford Cockburn and Jemima Mack

Death record of George Alexander Cockburn (grandfather of George SS Cockburn)

Death record of Norman Stratford Cockburn (father of George SS Cockburn)

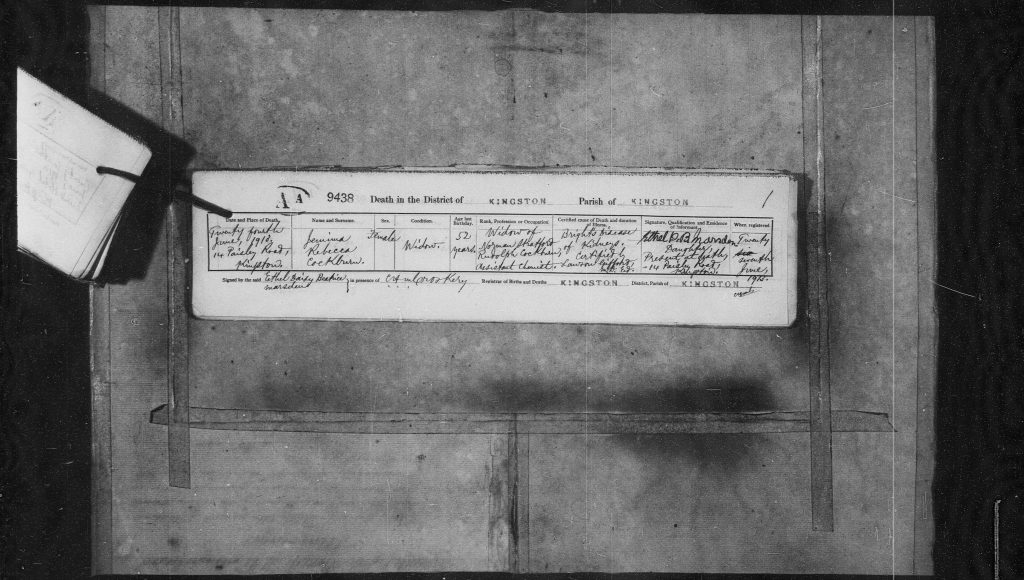

Death record of Jemima Cockburn

Photo-metal check request of George SS Cockburn, page 1

Photo-metal check, page 2

George SS Cockburn’s request for a new photo-metal check

Birth record of Erick Fitzgerald Cockburn

Birth record of Gilbert Leroy Cockburn

Screenshot of data from Pearl Lera Evering (nee Cockburn)’s Social Security (no digitalized image, from Ancestry.com)

1940 Census, Panama Canal Zone

1950 Census, Panama Canal Zone Source Information

Image Sources

Alamy. Mid-1700s map of Port Royal and Kingston Harbour. 24 Mar. 2016. The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Limited, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/24/story-cities-9-kingston-jamaica-richest-wickedest-city-world. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Civic Council Slates Listed.” The Panama Canal Spillway, 30 Oct. 1964, pp. 1–4, https://dloc.com/UF00094771/00482/images. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Civic Council Elections Nov. 9, 10.” Panama Canal Spillway, 5 Nov. 1965, pp. 1–4, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00094771/00535/zoom/3. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Cleary, JW. Kingston After 1907 Earthquake, Jamaica. 2 Feb. 2017. The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Limited, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/feb/02/jamaica-in-the-1890s-in-pictures. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Colon Methodists To Hold Quarterly Meeting Saturday.” Panama American, 11 Sept. 1958, pp. 3–3, https://dloc.com/AA00010883/02668/images/2. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Department of Operation and Maintenance. Town Maps of the Northern and Southern Districts – Silver City. University of Florida Digital Collections, University of Florida, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00000074/00001/images/11. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Eslava Flores, Carlos Alberto. Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción de Barichara – 1. Biblioteca Virtual Del Banco de La República, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/carlos-eslava/id/115. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Eslava Flores, Carlos Alberto. Catedral de la Inmaculada Concepción de Barichara – 2. Biblioteca Virtual Del Banco de La República, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/carlos-eslava/id/115. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Gente En La Noticia.” Panama Canal Spillway, 7 June 1963, pp. 4, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00094771/00410/zoom/3. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“JAMAICA TAXES EMIGRANTS.; $5 Required from Each Person Going to Panama Canal Zone.” New York Times, 17 Dec. 1905, pp. 22, https://www.nytimes.com/1905/12/17/archives/jamaica-taxes-emigrants-5-required-from-each-person-going-to-panama.html. Accessed 8 July 2024.

James Valentine & Sons. Street View, Kingston, 1891. 2 Feb. 2017. The Guardian, Guardian News & Media Limited, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/feb/02/jamaica-in-the-1890s-in-pictures. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Kingston Map 1. 2013. Jamaican Family Search, Jamaican Family Search Genealogy Research Library, http://www.jamaicanfamilysearch.com/Samples2/kgnmaps1894.htm. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“New Officers Take Posts at Meeting of Moonlight Club.” Panama American, 28 Apr. 1945, pp. 3–3, https://dloc.com/AA00010883/05572/zoom/2. Accessed 8 July 2024.

West Indies and Central America, 1910. 2009. Maps ETC, USF, https://etc.usf.edu/maps/pages/7600/7642/7642.htm. Accessed 8 July 2024.

FamilySearch and Ancestry.com Document Sources

Death of Edmund Cyril Stratford Cockburn – Kingston. Death Registers 1891, January 1892–September 1892 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5VT-9RBP?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1C-96S&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Death of Ethel Marsden – Kingston. Death Records 1964, 1965 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-994D-8LL1?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQVSR-VS81&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Death of George Alexander Cockburn, “Jamaica, Church of England Parish Register Transcripts, 1664-1880” • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6JLQ-F1QT. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Death of Jemima Cockburn nee Mack – Kingston. Death Registers , • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5VW-9419?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1M-W2J&action=view. Accessed 16 July 2024.

Death of Norman Stratford Cockburn – Saint Andrew. Civil Registrations 1902, 1904, 1903 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-95JR-ZGX?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP13-F7J&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Death of Norman Stratford Rudolph Cockburn – Cross Roads. Death Records 1953 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-894D-HHPZ?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQVSR-ZKKR&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Erick Fitzgerald Cockburn Birth Record – Catedral Inmaculada Concepción. Baptism Records • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GGBW-87R?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQG6X-3P81&action=view. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Ethel Daisy Beatrice Cockburn Birth Record – Kingston. Birth Records 1884 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-61X9-6RV?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXF1H-82X&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

George Stratford Seymour Cockburn Birth Record – Kingston. Birth Records 1889 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-6579-9TW?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXF18-96D&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Gilbert Carl Leroy Cockburn Birth Record – Catedral Inmaculada Concepción. Baptism Records • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GGBW-Z78?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQG6X-MF62&action=view. Accessed 8 July 2024.

Marriage Register of Ethel Cockburn and Walter Marsden – Kingston. Marriage Records 1905 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5V6-Z5D?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1V-CGB&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Marriage Register of Norman and Jemima Cockburn – Kingston. Birth Record Indexes 1880–1896 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5V5-QB9?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKP1W-DRF&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Norman Stratford Rudolph Cockburn Birth Record – Kingston. Birth Records 1885 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-X3S9-6SF?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXF14-Q99&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Pearl Lera Evering U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 – Ancestry.Com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/30281541:60901?tid=&pid=&queryId=0c75ca51-1a83-4623-a9d4-db0787e32182&_phsrc=Owz41&_phstart=successSource. Accessed 8 July 2024.

United States Census, 1950: Cristóbal. Census 1950 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHJ-5QH4-2SZK?view=index&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

United States Census, 1950: Cristóbal. Census 1940 • FamilySearch. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9M1-L7FW?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AK4K1-YC7&action=view. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

Other Sources

Barringer, T. J., and Wayne Modest. Victorian Jamaica. Duke University Press, 2018.

Chapin, Selden. “The Ambassador in Panama (Chapin) to the Secretary of State.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, 2024, history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1952-54v04/d640.

“Charlemount.” Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, UCL Department of History, 2024, www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/1690.

Cockburn-Hood, Thomas H. “The House of Cockburn of That Ilk and the Cadets Thereof.” Internet Archive, Scott and Ferguson, 1 Jan. 1888, archive.org/details/houseofcockburno00cockuoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

Cornish, Vaughan. “The Jamaica Earthquake (1907).” The Geographical Journal, vol. 31, no. 3, 1908, pp. 245–71. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1777429.

Cundall, Frank, et al. “The Handbook of Jamaica for …: Comprising Historical, Statistical and General Information Concerning the Island Compiled from Official and Other Reliable Records.” The Handbook of Jamaica for … : Comprising Historical, Statistical and General Information Concerning the Island Compiled from Official and Other Reliable Records., Govt. Print. Establishment, 1881.

Jamaica International Exhibition, 1891.Sciencens-15,217-217(1890).DOI:10.1126/science.ns-15.374.217.a

“Migration.” National Library of Jamaica Digital Collection, nljdigital.nlj.gov.jm/exhibits/show/colon-man-panama-experience/migration. Accessed 8 July 2024.

“Our History.” JPS, Jamaican Public Service Company, 2018, web.archive.org/web/20190209140743/https://www.jpsco.com/our-history/.

Senior, Olive. Encyclopedia of Jamaican Heritage. Twin Guinep Publishers, 2004, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofja0000seni, Accessed 8 July 2024.

“The History of Jamaica.” Jamaica Information Service, 2024, jis.gov.jm/information/jamaican-history/.

-

Rose N. Grimes

This post is part of a pilot student project created for the University of Florida class, Raising History from the Grave: Primary Historical Research in Literary Analysis and Public Humanities taught by Dr. Leah Rosenberg. The students focused on members of the Black Caribbean diaspora who worked on the Panama Canal or in the Canal Zone, the U.S. territory that surrounded the Panama Canal for much of the 20th century. These employees were originally classified as Silver employees because they were paid in silver currency as opposed to the Gold employees who were American citizens paid in gold currency. The term is still used today by both the community and scholars. The students worked with Pan Caribbean Sankofa, a community organization dedicated to preserving the history of Caribbean people in Panama, who identified community leaders as subjects for the project. Students consulted a wide array of archival materials in the Panama Canal Museum Collection and other institutions and learned how to use these resources to highlight individual accomplishments and connect lives to their larger communities through the digital humanities. For other posts, see Raising History from the Grave.

Setting the Scene

The year is 1905. A young girl sits on a crowded boat – one of the only girls amid a myriad of young men chatting enthusiastically about the journey ahead. They speak of gold, work, and wonder about what lies ahead in “Panama.” To the girl, it all sounds like a dream – leaving her family, friends, and the only life she’s ever known to travel over 1300 miles across the open waters to this mysterious place … “Panama.”

For the men around her, it’s a country bursting with opportunity and riches – or at least that’s what they had been told. But what about the young girl? No recruiters had come knocking at her door, flashing shiny gold coins with promises that she, too, could earn this wealth. The ship’s horn bellows, jolting the girl from her musings. She lifts her gaze and sees that the ship has begun to depart, the shores of Grenada shrinking smaller into the horizon. She watches intently until it disappears from view, a silent farewell to her past life. Finally, she turns her back from the receding horizon and looks to the future and the new life awaiting her in Panama.

This is likely what Rose Nickles Grimes faced as she entered the Panama Canal Zone. She was a woman whose work and contributions to the development of the Panama Canal had been lost to time – until now.

Arrival at Cristobal of S.S. Ancon with 1500 Laborers from Barbados, Deck Scene, September 2, 1909. Panama Canal Museum Collection. Gift of George R. and Marion Goethals. II.2024.12.132 Introduction

The voices and histories of Black women in the Panama Canal Zone are among the many that have been lost to time. For decades, the glory of the canal was reserved for America, a feat that launched the country towards its status as a world power. Only in recent times have the stories of the West Indian men who built the canal begun to be told, but women’s voices are still missing from the narrative. Behind the image of young and spry men laying the foundation for what is considered to be one of the “Seven Wonders of the Modern World,” were the women who laid the foundation for it all. Our team of three undergraduates has been researching Rose Nickles Grimes, a woman who moved to the Canal Zone from Grenada in 1905.

Her personal narrative, a document telling her story in first person as dictated to a granddaughter Valina, provided us with key facts about her life, such as her young years working as a midwife in Grenada, her marriage to Samuel Grimes, and her experience as a Black woman and mother in the Canal Zone. This narrative is the source for many of the facts provided here and gave us a jumping off point that led us to understand the broader context of the way West Indian women were essential to this American project. The many times we reference events from her life we are pulling information from this document. In this case what was not recorded told our team more than the records we did find about women. Most of the primary sources from the Canal Zone were written by men and focused on the male workforce. When women were mentioned, they were washerwomen, homemakers and healers. West Indian women were rarely mentioned. When they were, it was as low-level service provider, washerwomen, homemakers, and “maids.” The white U.S. government officials in the Canal Zone clearly saw West Indian women as of no importance. Yet, as Joan Flores-Villalobos argues in her book The Silver Women, West Indian women like Rose made it possible for the Canal to be completed by providing necessary labor and goods to the West Indian men workers and to the white U.S. employees and their families. They supported everything behind the scenes. Without West Indian women the Canal could not have been completed. The Black women white government officials and their wives looked down on were the backbone of the Canal’s creation.

St. George showing Fort George from Council Chamber, Grenada, West India Island. 1895. Early Years – Grenada, Traditional Healing and Spirituality

Rose was born in Grenada, during a period of widespread migration. Starting with the emancipation that occurred in Grenada in 1838, many people were looking to leave their past behind and search for a better life. Migration trends changed over the years, and “between 1885 and 1920, their preference was for Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Central America and Panama” (Phillip). This shows a broader trend of migration. For Rose, the push factor was her dad leaving to go to Panama to work on the canal when she was 14 years old. Then, in 1905, when Rose was 19 years old, her father called for her, feeling as though she could make more money in Panama. She was excited to finally get to go out and explore something away from home, and was on her way to Panama within six months.

Traditional healing practices and spiritual beliefs were also prevalent throughout the country in which Rose was raised. Based on scholarly studies of healing practices in Grenada and on her family’s oral histories, we know that these cultural experiences throughout her early life had a big impact on who she was as a person throughout her early life. In Grenada, healing practices often intertwine with strong spiritual beliefs. Patsy Sutherland’s article “Traditional Healing and Spirituality Among Grenadian Women” reveals that in Grenada, healing is not merely a physical act; it is also deeply intertwined with spiritual practices and beliefs. Sutherland looks at the major beliefs concerning healing across all of Grenadian history. She summarizes her holistic approach with the insight that healing is about bringing balance to the body, mind, and spirit, using what the earth provides. The article also discusses the reverence often held towards ancestors and their wisdom. Sutherland’s findings help to explain the profound significance of Rose’s healing practices for her family and community. This knowledge, combined with the work she did as an apprentice to a doctor, led to her developing the skills necessary to become the village midwife.

Much of the documentation we have on midwifery in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s are in the form of books on rules and regulations. This is an indication that government officials were in the process of pushing women out of this important medical profession and establishing doctors, usually men and often white, as the only legal providers of childbirth health care. Thus, an article from The Lancet titled “America’s triumph in Panama Three Years’ Medical and Sanitary Record in the Canal Zone” shares how “Miss B.M. Broadwood, honorary secretary and director of the Cottage Benefit Nursing Association, said that in starting the association she was advised of the undesirability of introducing certificated midwives into the country who might be tempted to take the place of medical men” (Leigh).

Another example of this type of regulation is the 1911 Executive Order issued by canal authorities that banned the practice of midwifery without proper licensing. Thus, whether medical men were ‘losing job opportunities’, they wanted to exert more control over the potential midwives of the community, or even just for sanitary concerns- this change would have directly impacted Grimes’ future.

Panama Canal Record, 1941. V. 1-34, no. 9; page 154

Rose continued to use her healing knowledge to treat her family and community despite these prohibitions. She used a lot of natural ingredients from the land to create remedies, as was more common back then. Additionally, she taught these skills to her children and grandchildren, and so her family went most of their lives without needing to go to the doctors. Her descendant, Art Walker, discusses these practices as he shares Grimes’ deep influence on his mother, and the lasting impact she has had on his life as his great-grandmother.

As for her spiritual beliefs, Rose did not believe in going to church. However, she did regularly invite the local priest over to discuss religious matters with him. She was very spiritual, though she did not identify with any particular religion. Art Walker discusses this further in this additional clip from his oral history:

You can view the entire interview here: https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00082255/00001/videos

Departure of laborers from Barbados for the Panama Canal Creating a New Life in the Panama Canal

Arriving at the Canal Zone at just 19 years old, Rose faced a difficult task: finding a job. In Grenada, Rose had been trained as a midwife and was confident in her abilities. However, as she went door to door offering her skill to potential employers, they simply laughed in her face. Unless she redid her entire education, Rose was out of luck for work in her sole profession. This was a grim reality Rose and many other educated Black women faced in the canal. She needed work, and quickly. With options severely limited, Rose settled on work as a laundress.

Many Black women in the Panama Canal found work in the service industry – often, this was the only valid route of employment available to them. Yet, once they overcame the hurdle of securing employment, they encountered an even greater challenge: racism, discrimination, and mistreatment. Joan Flores-Villalobos’ book, The Silver Women: How Black Women’s Labor Made the Panama Canal, details such issues. Unsurprisingly, Black women often found work in the hands of wealthy, White American employers, filled with the ignorant misconceptions of people of color they had carried with them from the States. A recipe for disaster, Black women were often overworked, underpaid, and under-appreciated, but their work was vital for the construction of the Canal and the laundering industry was no exception.

Laundry services in the Canal Zone held critical significance for several reasons. For one thing, they were imperative for maintaining the health and hygiene of workers in a tropical environment plagued by diseases like malaria and yellow fever. Clean and dry clothing helped prevent the spread of illness among the workforce, ensuring a safer working environment. It also provided comfort and boosted morale amidst the challenging conditions of the construction site – hot, humid, and miserable weather.

While laundry seems a simple task, The Silver Women highlights the physicality involved. Unlike today, washing machines were a rarity. So, women were often seen washing other people’s clothes by hand, using soap and water in basins or tubs, or washing by rivers. This was highly frowned upon by White women and used as another reason to belittle Black women. Although the exact details of Rose’s experiences in this toxic environment are unknown, she faced many of the challenges associated with it.

Nevertheless, Rose persevered through low pay and arduous labor for two years until 1907, when she found a job at a bakery. In 1911, Rose met a man named Samuel Grimes. Described by Rose as a tall and handsome man, Samuel had recently moved from Barbados – one of the thousands of young men who flocked to the Canal Zone in search of work. In fact, Samuel was one of the pioneering Barbadians to enlist in the Canal workforce, as the recruitment station in Barbados was established in 1905, just one year before his arrival. After two years of courting, the couple married and moved in together. Soon after, they had their first children, and following the customs of the time, Rose quit the bakery and began the arguably more demanding job of a wife and mother – child rearing, cooking, and cleaning were just a few of the responsibilities she had to take on.

Establishing a Home in Paraiso

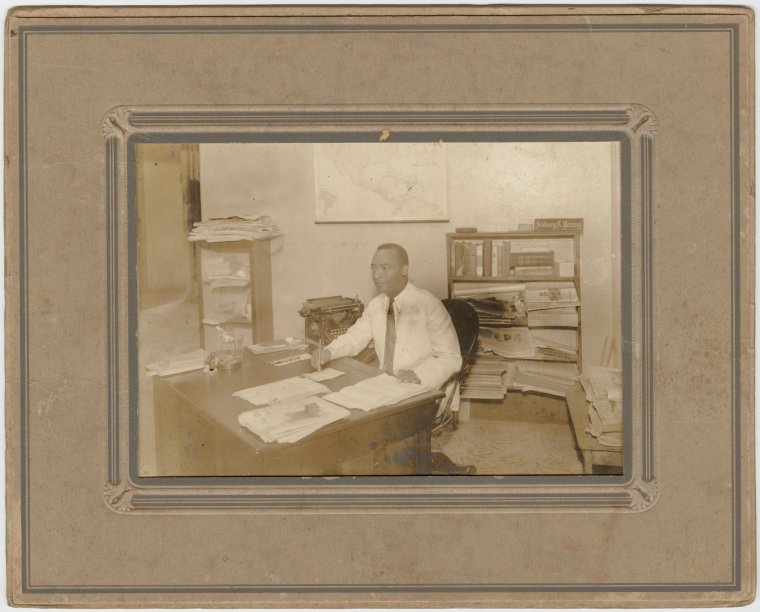

Rose’s family likely called Paraiso home between 1919 and 1936. The date she moved to the town is unclear, but her husband was working in the area by 1919. There are no further records after 1936 tying her to Paraiso. The family of Rose informed us that by late 1936, Samuel and Rose were able to buy acres of land and build a home in a small town called Chilibre (information provided by Carmen Grimes Eccles). Below is pictures of Samuel Grimes’ request for metal check issue, an application for photo metal check and a picture of the Pedro Miguel Post Office, where Samuel applied for his metal check.

Rose’s family likely lived in Paraiso because of her husband’s job in the town of Pedro Miguel. Pedro Miguel was home to a large set of locks on the Pacific side of the Canal used to keep ocean liners and container ships moving through the Canal. In the 1920 census, his job is listed as “Machine Helper.” According to Samuel’s metal check from February 1919 he worked with the Municipal Engineering Department as an Artisan “C”, earning 24 cents an hour. He was about 32 at the time. The Workman says Artisans are, “employees performing the duties of shop, building, construction, and other machines and artisans.“ It covers positions like blacksmith, molder, painter, drill runner, lineman, printing, carpenter, machinist, and mason. Samuel must have been trained and experienced to obtain this position.

In the July 1919, The Workman reported a wage increase for Artisan C to 27 cents, more than both Artisan A and B. The article says, “This rate may be granted only after the artisan has demonstrated that the quality and quantity of work is such as would, in the opinion of the foreman in charge, entitle him to a higher rate than that for Artisan B.”

Image: excerpt from the “New Rate of [Pay] for Colored Employees,” The Workman, 19 July 1919, p. 8

It is the highest-ranking position mentioned in the article. Later, in a 1930 request for a metal check issue, his age is listed as 44; he was still working for the Municipal Department as an Artisan. This time he is making 32 cents an hour.

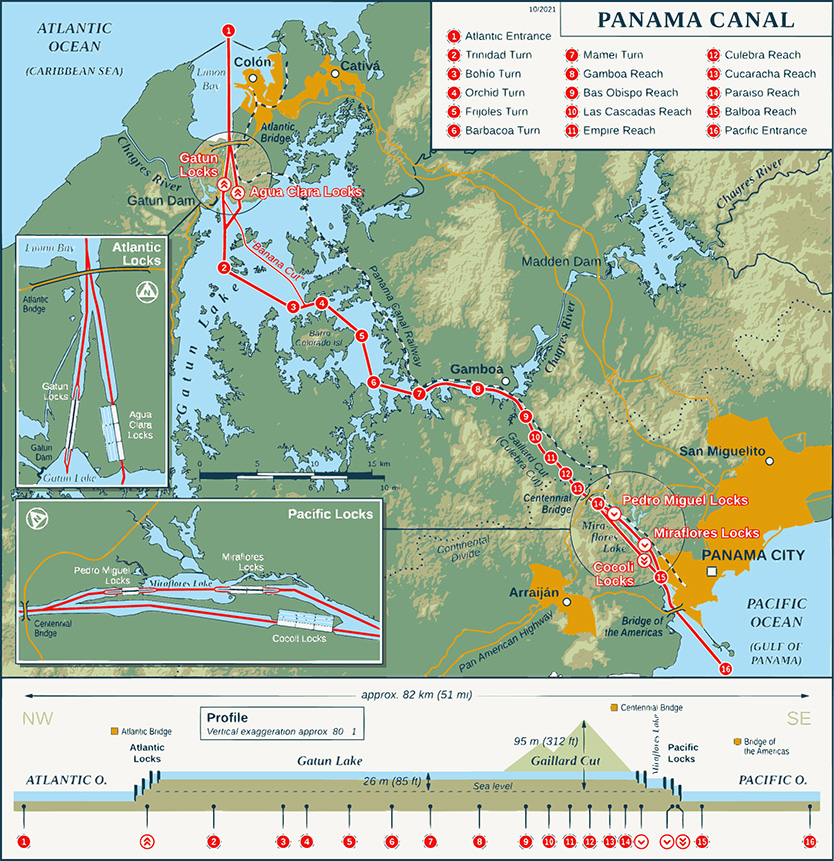

Panama Canal Map, 2012 Prior to 1919, when Rose likely moved to Paraiso, the town had been prominent – home to many Gold and Silver employees. The designation of Gold employee was largely reserved for American citizens and reflected the fact that they were paid in gold currency. Silver employees were predominantly West-Indian and were paid in silver currency. Rose’s family like arrived after 1918, when the white, Gold employees departed, and Paraiso became a Silver town. Located just north of the Pedro Miguel Locks, it served many purposes throughout its history. Paraiso was originally established by the French railroad which used it for light repair to trains and excavators during the French canal project. During the US Construction, Paraiso hung on the edge of excavation, so landslides were common. As work moved west in 1908, the town became mostly residential for employees working on the Pedro Miguel Locks and railroad workers. Two U.S. Presidents stopped in Paraiso during their visits to the Panama Canal – Theodore Roosevelt in 1906 and William H. Taft in 1910. In July 1913 the Canal was nearing completion as the Dredging Division decided to make Paraiso their headquarters. By 1918, most Gold workers had moved from Paraiso to Pedro Miguel, and the town became a segregated “Silver” town. Rose and her family lived here during this time, and could have been one of the more affluent families. Samuel’s job was the highest paid artisan position, while Rose contributed to the family financially through taking in laundry. Even though Samuel worked in the Pedro Miguel Locks, Paraiso was home to the silver employees. In 1936, the Dredging Division moved to Gamboa, which after a short abandonment, became a military post in 1939. Camp Paraiso, tasked with defending the Canal, closed in 1943 leaving behind barracks that were converted into family housing. During the 1950’s, Paraiso was considered one of the Canal Zone’s most modern communities. The town history provides context for Rose’s experience in the town and shows that it was an important location during the construction of the Canal. To see the locks Samuel worked on, use the arrows to view the slideshow.

The building circled on this census map is where Rose, Samuel and their family lived during the 1930 census in apartment G and H. The map is from the 1940 census, but we assume the numbering stayed the same between the two records. By 1940 the Grimes’ lived in a home they built, so it isn’t on this map.

Census Enumeration District Map, 1940 Some documents pertaining to Rose and her family mentioned they lived in Red Tank, another name for the Paraiso area. The origin of Red Tank is blurry. In a December 1953 edition of The Panama Canal Review, reports the town was then deserted but shares an account of how it may have gotten its name. In 1904, a timetable for the Panama Railroad showed a stop named Pedro Miguel Tank. At this stop, there was a big water tank, painted with red lead according to, “old timers, like William Jump.” The three towns, Red Tank, Paraiso and Pedro Miguel, seem to blur together in old articles and accounts of the area. The pictures below show examples of Silver housing.

Pictures of Paraiso from the Panama Canal Collection at the University of Florida Family Life

All of Rose’s children were born in Paraiso, according to census data. The oldest of six, Silvia Valina Grimes Tappin, was born in 1916, followed by George (1918) and John O. (1919). The second three children were James O. (1920), Mabel L. (1923), and Alice B. (1924). The Grimes’ family continued to live in Paraiso at least until 1930 when the household appears on the 1930 census. We were unable to find any additional official documents with Rose until her death certificate. During this time, several chaotic world-wide events took place – World War I, a big strike, a coup in Panama in 1930, and the Great Depression. Through it all, Rose was able to help her neighborhood. Rose explained to her granddaughter that she was called “Señora Rosa” by her community and that the name was, “bestowed by the many people I was able to help during the depression era.” She raised a family, contributed to the household financially, and was a pillar of the neighborhood. This time was not without trial though. She says, “When the crash came in 1929, I lost every cent that was in the bank.”

Even though the world around her was tumultuous, Rose’s responsibilities did not end – her children still needed to be fed. While Rose had originally stopped working outside the home once she and Samuel began raising a family, she resumed taking in laundry as an independent contractor. According to Flores-Villalobos, many Black women took this route as independent contractors, not just in laundering, but with selling food or other goods. As Flores-Villalobos writes, “West Indian laundresses often set their own prices and could reportedly make as much $6 in one day, equivalent to a Silver laborer’s weekly pay. For comparison, a white Gold Roll nurse earned $50 a month” (pp. 117). This provides key insight into how much Rose contributed to her family home as a homemaker. Of course the labor that involves is already a full-time job, but in addition she brought income as a laundress – characteristics of a self-determined, driven, business-savvy, and intelligent woman! In the midst of her already demanding schedule within her own family, Rose also provided food for those in need from her community. She said, “if anyone came to the house asking for food, there was always something for them… Regardless of how much or little we had, it would [be] shared,” truly embodying the beloved title of Señora Rosa.

Panamanian Forest, 1870s (Angrick)

Map of Panama Canal with Chilibre marked When the banks returned the money their family had lost in the 1929 crash, Rose and Samuel started building their own home in Chilibre. Chilibre, at the time, was a bushy or forested area which was good for the farming of grains, vegetables, fruit trees, root vegetables, bananas, cane, and yucca. The couple raised cows, goats, chickens, bees, and ducks in addition to the produce previously mentioned (information provided Carmen Grimes Eccles). They built a house here, which was finished in 1939 and celebrated Christmas in their new home. Rose notes that the hardest part was building the well – the men spent 6 months working on it. Her adult sons contributed to the construction of the home; son James O even added his carpentry skills. Finished in 1939, the house took 18 months because most of the material was acquired from the American government in the Canal Zone. The government has strict specifications. If the material and equipment they bought did not meet regulations the government would throw it away, even though it was nearly new. Most families lived in government housing, so this is unique. Units were built for bachelors, single women, and families by the US government, not by the individual families themselves. Due to Samuel’s higher position and Rose’s income that allowed them to build a home.

After her family moved into the new house, her granddaughter Valina moved in with her. Rose extolls all of Valina’s equalities, showing her to be a doting and loving grandmother. Valina, like her grandmother, leaves everything she knows to immigrate to a new country for opportunity. On Christmas Day 1956, Valina announced she was going to university in the United States. Like Rose leaving her homeland, never to see family in Grenada again, Valina repeated history by taking a brave step away from home. Her plane took off August 7, 1957 and Rose never saw her again. Rose closes her personal narrative saying, “Thursdays child has far to go.” She believed in her granddaughters potential and knew Valina would be resilient in a new place, just like herself.

A Lasting Legacy

We know Silvia married a man named Bindley B. Tappin (Social Security Numerical Identification). Together, they had three children – Valina C. Tappin Walker (1937), John E. (1939), and Joel W. (1941). Their second child George O. married Ivy Whittier and were parents to seven children. John O. marries Violet and they had 6 children. James O. and Carmen also have 7 children (their daughter Carmen Grimes Eccles has gifted the Grandmother Rose Grimes story to the University of Florida for us in collaboration with this research project). Mabel L. had no children and Alice B. had three with Baltimore Brown. This family tree shows Rose’s extended family and all the lives her legacy touched.

Rose passed away on the 12th of November, 1970 in Panama City, Panama (Gorgas Hospital Mortuary Registers). Her grave can be found Corozal cemetery in grave number 4.

We would like to thank Carmen Grimes Eccles for all the support and information she shared with our team as we wrote this post. It was invaluable to us during the process and provided insight that allowed us to understand Rose better. Thank you so much!

-

Luther McDonald Hartley

This post is part of a pilot student project created for the University of Florida class, Raising History from the Grave: Primary Historical Research in Literary Analysis and Public Humanities taught by Dr. Leah Rosenberg. The students focused on members of the Black Caribbean diaspora who worked on the Panama Canal or in the Canal Zone, the U.S. territory that surrounded the Panama Canal for much of the 20th century. These employees were originally classified as Silver employees because they were paid in silver currency as opposed to the Gold employees who were American citizens paid in gold currency. The term is still used today by both the community and scholars. The students worked with Pan Caribbean Sankofa, a community organization dedicated to preserving the history of Caribbean people in Panama, who identified community leaders as subjects for the project. Students consulted a wide array of archival materials in the Panama Canal Museum Collection and other institutions and learned how to use these resources to highlight individual accomplishments and connect lives to their larger communities through the digital humanities. For other posts, see Raising History from the Grave.

Commissary Pick-up Train at Gatun. June, 1911. Panama Canal Museum Collection. Gift of Mickey Fitzgerald and Carol Miller. II.2019.49.1. Beginnings

1920 Census

1930 Census

1940 Census Luther Hartley’s parents were from Clarendon, Jamaica, a rural parish famous for its beauty and its varied agricultural crops. However, in the second half of the nineteenth century when Luther’s parents were likely living in Clarendon, the circumstances were very difficult. Planters refused to sell land to peasants, and the Jamaican colonial government did not invest in the roads, schools, or hospitals ordinary Jamaicans needed to transport their crops or raise their children. Jamaica’s sugar industry was in collapse and bananas had yet to emerge as the country’s major industry. Wages were low and unemployment high. Many Jamaicans were poorly housed. Many suffered from malnutrition. These circumstances may have influenced Nathan Hartley and Susana Williams to leave for Panama (James 19-21).

In addition to his reputation as a center for agriculture, Clarendon is known as the birth place of prominent Jamaicans such as the early Rastafarian leader Leonard Howell (1898-1981) and the author Claude McKay (1890-1948) (The National Library of Jamaica).

Life on the Railroad

Source: Ernest Hallen (American, 1875-1947), Culebra Cut. Looking North, between Contractor’s Hill and Gold Hill. June, 1911. Panama Canal Museum Collection. 2014.160.16. Hartley joined the workforce of the Panama Railroad when he was around 18 to 20 years old and remained on the workforce for over 40 years, until he retired in 1954. He worked as a Brakeman, a flagman and “track shifter,” or” “switchgear” (Arcelio Hartley). The Panama Railroad was one of the most important and dangerous aspects of the Canal’s construction. In 1904, the Panama Canal Railroad recruited workers to remove the “spoil” – mud, rock, and other material – from the Canal site so work could continue uninterrupted. The numerous trains moving both people, freight, and debris across the zone each day, the heat, the noise, the necessity of continually moving the tracks, and danger of landslides all made Hartley’s job perilous.

In 1910, the trains carried over 2.25 million passengers and 1.25 million tons of commercial freight. The trains also carried nearly 40,000,000 tons of debris away from the construction zone. At this time, the Panama Canal Railroad was the busiest railway in the world, with 574 trains passing by each day (The Panama Railroad). This was impressive, yet nonetheless made work particularly treacherous.

Each job on the railroad was dangerous due to the number of trains and the conditions in which the men worked. The responsibilities of these workers, which included shifting tracks and directing trains amid the environmental rumble of the famous Culebra Cut, were daily challenges. Landslides were also common factors in deaths or injuries. An estimated 5,609 laborers were killed during the project, and an even higher amount of life-changing injuries occurred (“The Panama Canal’s Forgotten Casualties.”). Accidents were so common that the Panama Railroad Company Committee had “a comprehensive and continuous accident prevention program” (Panama Railroad Company Committee). The possibility of being injured or killed on the job was very high.

This video from 1912 depicts the American mindset towards the workers of the Panama Canal and the scope of the project. To the filmmakers, the Canal was not as dangerous as it was “famous” and “powerful.” They mention the statistics of the shovels made in America to build the Canal, but do not mention the lives lost during construction. Additionally, they speak in awe of the Culebra Cut and Cucaracha Slide’s fame without mentioning how each was responsible for the death of many workers. The language used to describe these two included the words, “annoying and disturbing.” Additionally, Theodore Roosevelt is documented as a project manager, despite only having visited the Canal once before it’s completion. The video displays little regard to the project’s effects on the workers and the environment, ultimately narrating from a substantially limited perspective. Brakeman and Flagman

Luther Hartley’s metal check certificate. This document indicates his occupation, location, and rate of pay while working on the railroad. All employees had a metal check issued to them. Image Source: “United States, Panama Canal Zone, Employment Records and Sailing lists, 1905-1937,” database with images, FamilySearch, Luther McDonald Hartley, 10 Nov 1930; citing piece/folio 32538, Metal Check Issue Cards,1930-1937, 7226555, NARA record group 185, National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri. In the report of a 1911 accident, Hartley is listed as a brakeman; on his metal check, dated nearly two decades later, he is classified as a flagman. The Panama Railroad Rules and Regulations (1912) indicates that these were very closely related positions: the Rear Brakeman was also known as the flagman (148). Both were classified as “trainmen” and reported to the Train Master and served under the conductor while on the train. The Head Brakeman was responsible for the front of the train and the flagman was responsible for the rear of the train. In addition to “tending to the brakes,” brakemen had many responsibilities, including displaying signals, attending to lighting and ventilation for all cars, assisting the conductor with the passengers (including making sure that they did not violate regulations) and in all things pertaining to the safety of the train, including stopping the train if parted and the reuniting of the cars (148-149). (See the description from Panama Railroad Rules and Regulations below.)

It is his duty to attend to the brakes; take care of and properly display train signals; attend to the lighting and ventilation of all cars and assist the Conductor … in all things requisite for the prompt and safe movement of the train and the comfort of the passengers

Passage from Rules and Regulations that explains that the Rear Brakeman “is known as the flagman.” (p. 149). This indicates that Hartley may have held the same position before and after his accident as he was listed as a brakeman in the report of accident and as a flagman on this metal check created almost two decades later. If the train should part, he must immediately stop the rear portion and send forward the most reliable person he can secure to make STOP signals until the front portion comes back while he protects the rear.

Flagmen like Luther Hartley used specific flags and lamps to indicate the direction, time of day, and whether workers were present while the train traveled. The colors were green, white, blue, and red (Panama Railroad Company Committee 56). For example, the flagmen would display a blue flag to signify that men were working around the train; due to the high risk of danger surrounding the job, workers were the only ones permitted to remove it (Panama Railroad Company Committee 56).

Workers at a rock slide in Culebra Cut, one of the most common reasons for injuries among railroad employees. Landslides often caused equipment and train cars to fall, causing even more injuries. Image source: Ernest Hallen (American, 1875-1947), Culebra Cut. Toe of Rock Slide, South End of Gold Hill, Showing Wreck of Steam Shovel #224, 1913. 2003.100.43.53. Note the man in the center of the photograph is missing an arm. Disabilities within the Workforce of the Panama Canal

A train on the Panama Railroad passing through Pedro Miguel, 1904-1914. Panama Canal Museum Collection. Gift of Brad Wilde. II.2021.36.106 At 10:52 am on December 16th, 1911, at the age of 21 years old, Hartley was working as a brakeman when an accident occurred at Pedro Miguel that crushed his foot. As a result, his leg was amputated (Personal Injury Register Book). Arcelio noted that his grandfather lived on the Atlantic side of the Canal in Colon, and the accident occurred on the Pacific side of the canal and demonstrated how far workers might travel in the course of their work. Hartley was one of over 5,000 workers the Canal authorities reported as injured on the job in 1911, the year with the highest recorded number of worker injuries during the construction (Leiffers).

This traumatic event altered the rest of his life both physically and financially. In addition to the physical pain, Hartley had to navigate the legalities and payments of his prosthetic. Luther Hartley faced many difficulties in addition to the physical pain, including petitioning the Canal administration for a prosthetic leg. Hartley retired from this position as a flagman in 1954 at the age of 64 (Arcelio Hartley). He worked with a prosthetic leg throughout his career of 40 years. Aside from the prosthetic, he did not receive disability compensation.

Audio clip: Arcelio Hartley speaks on Hartley’s struggle to obtain compensation for a prosthetic leg after the accident (Hartley). This account highlights the constant dangers and discrimination workers faced while on the railroad. Hartley paid for his first prosthetic leg, despite the Isthmus Canal Commission’s responsibility for supplying prosthetics needed for work injuries. This prosthetic was described as a ‘cork leg’ and he received it about a year after the accident. (Arcelio Hartley).

In a letter dated 1917, Luther requested that he be provided a new artificial leg for free. Another letter from the late 1920s indicates that he received a new leg in 1922 but that he suffered pain because numerous components of the leg were broken. In 1952, Hartley had to, once again, request that his prosthesis be replaced.

Click on the letters below. Thank you to the Hartley Family for sharing them with us.

Prosthetics in High Demand

Due to the substantial amount of accidents, the Isthmus Canal Commission anticipated the need for prosthetics in the Canal Zone. In 1904, a steady increase of extreme work-related injuries began. Instead of altering working conditions, Canal authorities focused on improving the availability of prosthetics in order for the employees to continue routine work (Guffey and Williamson 61).

Image Source: Photo Album of Fred Lyon. II.2022.48.2. Panama Canal Museum Collection. Gift of the Sturges Family. II.2022.48.2. “Operation Room-Colon Hospital,” 1910. This photograph depicts an operating room from Colon Hospital. Hartley’s amputation would have occurred in a room similar to this. Several companies provided prosthetics to injured Panama Canal workers. One company in particular, A. A. Marks, was a prominent supplier for Canal workers. Though they had previously produced prosthetics, A. A. Marks found it imperative to modify their products for Canal workers (NYAM: History of Medicine and Public Health).

An indication of the prevalence of workplace injury among Black workers, also called Silver workers because of their classification as non-American employees paid in silver currency, is the fact that A. A. Marks produced prosthetic limbs for Black and Brown workers (Guffey and Williamson 65). Historically, white has been the most prevalent skin tone for prosthetic limbs, but in advertisements referencing the Panama Canal that was not the case.

Image Source: Johanna Goldberg, NYAM Center for History, 2014. A. A. Marks Co., Manual of Artificial Limbs, 1906. In 1906, A. A. Marks Co. published Manual of Artificial Limbs, which served as both a manual and advertisement for the company. One caption says, “He retains his balance with no perceptible effort or awkwardness.” Railroad companies would take particular interest prosthetics that would not interfere with workers’ duties and/or efficiency. Two years later, the Isthmian Canal Commission started supplying these artificial limbs to Canal workers. By 1912, over 200 prosthetics had been distributed to workers suffering from work-related injuries (Guffey and Williamson 64).

A. A. Marks’s success at the Canal eventually provided them with an opportunity to advertise their product nationwide – doctors could even specifically request their company’s prosthetics for use.

A.A. Marks prosthetic advertisement to the Panama Canal that circulated in the early 1900s. (American Medicine 19 no. 5, May 1913: 5 cited in Leiffers)

There were several preconceptions of these commonly used prosthetics. One of these is the use of the term “cork leg.” However, according to A. A. Marks, the term “cork leg” was a misnomer because cork was never used as a prosthetic material due to its insufficient resistance to external forces. The term ‘cork leg’ was used synonymously with prosthetic leg and was possibly derived from peg legs, one of the first versions of the prosthetic leg. Cork was often used as insulation to the peg (Marks 18). Hartley’s prosthetic more than likely had rubber. By using rubber, A. A. Marks was able to increase durability, and they used it in all prosthetic models available at the time of Hartley’s accident. As the popularity of prosthetics spread, an increasing number of workers were able to return back to work.

Workers Compensation in the Canal Zone

The U.S. policy on benefits for disabled workers was complex and changed over time. The Isthmian Canal Commission began giving compensation to Silver workers for disabilities caused by work accidents in 1907 when workers were offered 30 days of pay. The ICC increased these benefits in 1908, 1914, and 1916 when employees were offered up to 2/3 lost earnings if the worker could prove that he was not at fault for the injury and that it occurred during his work time. In 1917, a special fund for “alien cripples” was established, but it required that employees return to their home countries, which many were unwilling to do, especially as the funds offered were often relatively small in comparison to the injury sustained and the men’s long-term financial needs (Leiffers).

The U.S. Congress repeatedly debated the policy for compensation and pensions for disabled Canal workers and changed the policy several times during Luther Hartley’s lifetime. There are no records indicating that Luther Hartley received monthly compensation as a result of his disability while he worked.

Audio Clip: Arcelio Hartley recounts that his grandfather received $5 a month and a box of dry food items such as powdered milk after he retired in 1954. This was not in recognition of his disability but rather provisions made for Silver workers who were not included in the official pension system. 1936 Hearing

After much delay, the issue of compensation for disabled workers was brought to the attention of a United States Congressional Committee. In February of 1936, there was a Congressional Hearing on the Superannuation Disability Pay and Disposition of Certain Lands within the Panama Canal Zone. They considered which workers would be eligible and how much they would be compensated. Superannuation Disability Pay is compensation for retired workers who were disabled on the job; this was often done by taking the current base pay and adding a lump sum on top.

The issue was that disability compensation was not technically mandatory for relief; it was on a “may pay” basis for disabled workers. The hearing discussed this may pay to become “shall pay,” with a goal of guaranteeing $125 a month to retirees and an additional $1 – $25 a month for individuals with disabilities (United States Senate 1936).

Image Above: A page from the U.S. Congress Committee 1936, where disability pension was discussed for one of the first times in the Canal Zone. Source: United States Senate. Panama Canal, Superannuation Disability Pay and Disposition of Certain Lands. Congressional Hearing, Jan. 31, Feb. 13, 1936.

Audio clip: : Arcelio Hartley explains that Luther was able to work after his accident. Casma Henlon who interviews him notes that Luther’s situation was somewhat unusual. The U.S. often “discarded” Silver employees who were injured on the job rather than offer disability compensation (Hartley). 1953 Hearing

In 1953, a congressional hearing was held on “Increased Benefits to Disabled Alien Employees of the Panama Canal.” Representatives of the Panama Canal Company met on July 23, 1953 in an attempt to pass H.R. 5861. If passed, the bill would increase the amount of relief paid to disabled alien employees of the Canal Zone government from the present rate of that time at $1 per month for each year of service to $1.50 per month for each year of service. There would be an increase in the maximum benefits from $25 a month to $45 a month.

Payments before this were under the act of July 8th, 1937, which made disabled employees serve at least ten years of work before getting relief (United States Senate 1953). The hearing of 1937 was quite similar to the hearing of 1936, because 3,200 disabled workers were receiving $25 a month (United States Senate 1937). It is unlikely that Hartley was one of them.

Source: United States Senate. To Amend the Act Approved July 8, 1937, Authorizing Cash Relief for Certain Employees of the Canal Zone Government. Congressional Hearing, 1953-07-28. N.p., 1953. Print.

A major push for change was enacted in part by the concern that if individuals did not receive a beneficial amount, they would leave and cause a decrease in the number of available workers. The actual process of establishing this policy was long, and not everyone saw its effects. It is important to understand the slow-moving progress of equality for Canal workers with disabilities and equally important to recognize that so many who were disabled, like Luther Hartley, did not receive what was promised.

Luther Hartley’s Legacy

Despite facing hardship at the Panama Canal, Hartley lived a successful and vibrant life. He was married to Ethel Walters of Jamaica and had three children: Eveline, Hanrow, and Gornett. Luther enjoyed hunting and had a property in Rio Rita where his grandchildren played.

Gornett Hartley, Luther’s son, followed in his father’s footsteps and worked on the Panama Railroad for many years. In an article for The Panama Canal Spillway he describes starting as an “errand boy” in 1939 and holding several other positions – “always…with the Panama Railroad.” (The Panama Canal Spillway, April 2, 1979)

Gornett Hartley, Certificate of faithful service during WWII, 1946.

Gornett Hartley, The Panama Canal Spillway, April 2, 1976. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/uf00094771/01067 Arcelio Hartley, Gornett’s son and Luther’s grandson, spent his career with the Panama Canal on the water instead of the rails. Arcelio rose to the highly regarded and difficult rank of Panama Canal Pilot, earning the respect of his colleagues and community. But his work outside the monumental waterway that his grandfather helped build was perhaps his greatest tribute to the generations that came before him. In 1997, then Port Captain Hartley, was honored for his contributions to the Atlantic-side community, described by others as “counselor”, “mediator”, “father”, “godfather”, “advocate”, and “friend”. He continues to give his time and expertise to organizations committed to preserving the history of the West Indian community in Panama, currently serving as the President of SAMAAP, the Society of Friends of the West Indian Museum of Panama, the Vice-President of CGM, The Corozal, Gatun, Mt. Hope Cemetery Preservation Foundation, and is a Director of Pan-Caribbean Sankofa.

Two of Luther Hartley’s grandchildren, Armando Hartley and Arcelio Hartley, have greatly helped this research project by lending documents and vital information. With this information, we were able to learn who Luther Hartley was, document his legacy, and understand situations other workers like him had gone through.

Luther McDonald Hartley passed away in a hospital in Coco Solo, on February 4th, 1962 before real change could be made (The National Archives). His final resting place is located in Mt. Hope Cemetery in Colón, Panama.

Source: Find a Grave. Mt. Hope Cemetery in Colón, Panama. EST. 1908., 29 July 2009, Accessed 26 Apr. 2024. Print. Words of Thanks and Dedication

We would like to thank the Hartley Family for all of their help, information, and stories they shared with us as we created this blog. We would also like to thank Dr. Leah Rosenberg, as well as Dr. Betsy Bemis and Mr. John Nemmers at the University of Florida’s Special and Area Studies Collections, for their invaluable guidance and aid in creating this historic blog. A very special thanks is due to Dr. Caroline Leiffers who provided the information about Luther Hartley’s injury from her research of the Personal Injury Register Books held in the Records of the Panama Canal at the National Archives.

Our work is dedicated to Luther’s ancestors, the many others who are connected to the Panama Canal’s construction, and those who seek the truth regarding one of the biggest projects in history.

Sources:

A field of tobacco, May Pen, Jamaica. [Date not indicated] Keystone-Mast Collection.

Owning Institution: UC Riverside, California Museum of Photography. Calisphere. April 26 2024

Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/kt7n39p9zr/Edwards, Kitty. “St Peter’s Anglican, Alley, Vere, Clarendon.” Jamaican Ancestral Records, 12 Mar. 2014, jamaicanancestralrecords.com/parishes-2/clarendon-2/st-peters-anglican-alley-vere-clarendon/. Accessed 26 Apr. 2024.

Ernest Hallen (American, 1875-1947), Culebra Cut. Toe of Rock Slide, South End of Gold Hill, Showing Wreck of Steam Shovel #224, 1913. 2003.100.43.53.

Find a Grave . Mt. Hope Cemetery in Colón, Panama. EST. 1908., 29 July 2009, images.findagrave.com/photos/2009/209/CEM47067481_124886326191.jpg?size=photos1024. Accessed 26 Apr. 2024.

Goldberg, Johanna. “A. A. Marks Company.” Books, Health and History, NYAM History of Medicine & Public Health, 19 Dec. 2014, nyamcenterforhistory.org/tag/a-a-marks-company/. Accessed 19 July 2024.

Hartley, Arcelio. Arcelio Hartley Oral History Interview. Pan Caribbean Sankofa and the Panama Canal Museum Collection. (2/1/2024).

Hartley, Armado. Armado Hartley Oral History Interview. Pan Caribbean Sankofa and the Panama Canal Museum Collection. (2/17/2023).